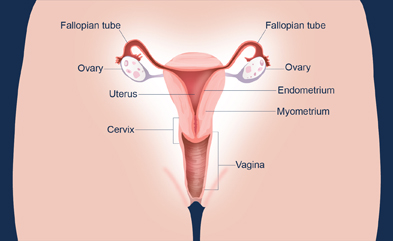

Menstruation (pronounced men-stroo-EY-shuhn) is normal discharge of blood and tissue from the uterine lining through the vagina (see diagram) that occurs as part of a woman's monthly menstrual cycle. Menstruation occurs between menarche (pronounced muh-NAHR-kee), a girl's first period, and menopause, when menstrual cycles end.1 The average menstruation time in normally menstruating women is about 5 days.2 In the United States, most girls start menstruating shortly after 12 years of age.3

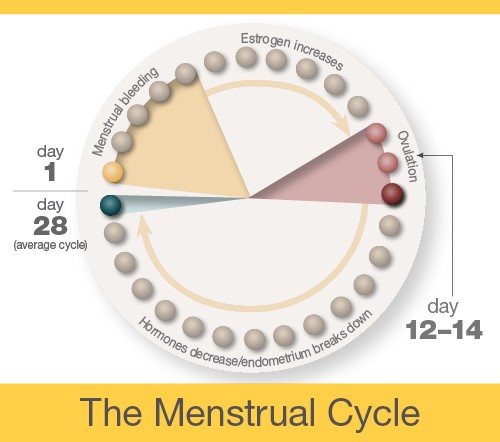

The menstrual cycle is the monthly process in which female hormones stimulate an ovary to release an egg, thicken the lining of the uterus to support a pregnancy, and then cause the uterus to shed this lining (through menstruation) if there is no pregnancy. The average menstrual cycle is 28 days, but this varies between women and from month to month. In teens, the menstrual cycle can range from 21 to 45 days, but for most women, it is 21 to 35 days.3

Day 1

The first day of bleeding is considered the first day of the menstrual cycle. After bleeding ends, usually around day 5, levels of the hormone estrogen begin to rise. The rise in estrogen causes the lining of the uterus to thicken as it prepares to hold a fertilized egg. At the same time, the changes in hormone levels cause follicles (the sacs in the ovary that contain eggs) to grow and mature, in preparation for one follicle to go through ovulation.

Ovulation

Around day 12 to 14 in an average 28-day cycle, the egg is released from a follicle on the ovary in a process called ovulation (pronounced ov-yu-LAY-shuhn). Ovulation can occur anywhere between 10 and 21 days after the first day of a woman's menstrual cycle. A woman can tell when she has begun ovulating using several methods, including at-home tests that measure levels of luteinizing hormone (LH) in the urine and keeping track of her body temperature, which typically rises slightly at ovulation. At mid-cycle, some women experience pain on one side of their pelvic area; this pain is called "Mittelschmerz"4 (meaning "middle pain," because it occurs in the middle of the cycle) and may be a signal of ovulation.

If a pregnancy does not occur, decreasing hormone levels signal for the lining of the uterus, called the endometrium, to be shed during menstruation.

The endometrium builds up and breaks down during the menstrual cycle. The endometrium is thickest halfway through the 28-day cycle. Then, if there is no pregnancy, it breaks down. This breakdown causes the bleeding of the menstrual phase. This diagram illustrates an average 28-day cycle.

Fertilization

After ovulation, the egg moves down the fallopian tube. The sperm can fertilize the egg at this point. After the sperm is ejaculated into the vagina, it moves into the cervix and through the uterus into the fallopian tube. Sperm can live up to 5 days in a woman's body.

If fertilization occurs, the newly formed embryo travels through the fallopian tube into the uterus, where it implants in the wall of the uterus. If fertilization does not occur, the egg naturally breaks down, and the uterine wall is lost in the form of menstrual bleeding.

Implantation

The embryo must successfully implant into the thickened wall of the uterus for the pregnancy to occur. The embryo first attaches to the wall of the uterus around 5 or 6 days after ovulation. It becomes more firmly implanted between 6 and 12 days after ovulation. Implantation causes a release of hCG—a hormone that signals the body to change to support the pregnancy. This hormone is what a pregnancy test detects.

Citations

- Sweet, M. G., Schmidt-Dalton, T. A., Weiss, P. M., & Madsen, K. P. (2012). Evaluation and management of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal women. American Family Physician, 85, 35–43.

- Dasharathy, S. S., Mumford, S. L., Pollack, A. Z., Perkins, N. J., Mattison, D. R., Wactawski-Wende, J., & Schisterman, E. F. (2012). Menstrual bleeding patterns among regularly menstruating women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 175, 536–545.

- McDowell, M. A., Brody, D. J., & Hughes, J.P. (2007). Has age at menarche changed? Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999-2004. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 227–231.

- Krohn, P. L. (1949). Intermenstrual pain (the "Mittelschmerz") and the time of ovulation. British Medical Journal, 1(4609), 803–805. Retrieved September 27, 2016, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2049988/?page=1

Perimenopause

Perimenopause BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP