The NICHD seeks to use its hard-earned research experience with HIV/AIDS to tackle other infectious diseases

The Maternal and Pediatric Infectious Disease Branch (MPIDB) was formed in 1988 as the Pediatric, Adolescent, and Maternal AIDS Branch. At that time, its mission was to support and conduct domestic and international research on the HIV/AIDS epidemic with a special focus on infants, children, adolescents, and women.

Since then, the Branch has led the way in research aimed at finding better ways to treat and prevent HIV infection in these populations. One noteworthy success story is its work on preventing HIV transmission from mother to child. Now the Branch is taking the lessons learned from its HIV/AIDS research and applying them to the challenges posed by HIV-associated co-infections, such as tuberculosis, hepatitis, malaria, and other infectious diseases.

We recently spoke with Rohan Hazra, M.D., the MPIDB's new chief, about some of the remaining challenges and opportunities in HIV/AIDS research and how the Branch is taking on other infectious diseases.

How did you first get interested in HIV/AIDS research?

I was trained in pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Boston Children's Hospital. While there, I worked in a laboratory on tuberculosis and other mycobacteria. I liked the lab but did not love it, so I started looking for jobs that were more clinically oriented. One position that became available was a National Cancer Institute (NCI) intramural research position in pediatric HIV. During my training, I had looked after children with HIV, so I had some clinical background and experience with the disease. This new work allowed me not only to provide patient care but also to do research. I moved my family down from Boston to take that position, and that is how it started.

The training in the NCI intramural program was great for a young investigator. I developed and ran research protocols, but I also got a lot of experience in the clinical side. I was taking care of sick HIV-infected children and adolescents but at the same time also doing rigorous clinical research. This was a very hands-on environment.

That period gave me an excellent background, training, and experience for my current position, although today I have very little actual hands-on patient care. Instead, I am overseeing and helping to lead pediatric HIV clinical research both here in the United States and around the world. Hopefully, that earlier hands-on experience makes me better in what I am doing now.

Much of your research has focused on the long-term effects of HIV on young people infected with the virus as infants. What are some of the unique health challenges these individuals face?

HIV-infected youth have a chronic condition, and they have to be on medication. As long as they can take and tolerate their antiretroviral drugs, their health can be quite good. The tremendous effectiveness of today's antiretrovirals is actually one of medicine's big success stories. These young people grew up at a time when they were not expected to survive, but now they have the potential of a normal life span.

The problems they face are instead issues of being stigmatized or issues related to coming from an HIV-affected family with parents or siblings who are sick or who have died. Often they face socioeconomic disadvantages. I think we all know that if people have economic stress in their lives, their day-to-day survival can take precedence over making sure that their prescriptions are filled. If you must use your limited funds for copays, you can't use that money for other needs. In some ways these other challenges can lead back into having poor health—psychosocial problems can also make it so they cannot take their antiretrovirals. And if they cannot take their medication, they will have substantial health problems.

How is research helping to improve the health and well-being of these youth?

First, appropriate testing of new antiretroviral medications in infants, children, and youth is critical research. Much of this research is done through our research networks, although some of it is investigator-initiated, grant-related research. Antiretroviral medication continues to improve. Many new medicines can be taken once a day and have less toxicity than older ones. However, they need to be tested in infants, children, and adolescents. That is a major Branch focus.

We are also following our cohorts into young adulthood to find out if there are any long-term effects of antiretroviral medication. For example, there is some evidence of premature aging in adults on antiretroviral medication, but we don't know if antiretrovirals cause premature aging in youth. If the standard time for cardiovascular problems or a heart attack is in a person's 50s, but we see such problems in people's 30s when they've been infected with HIV around birth, I would have to call that premature aging. They may be at risk for such complications, and we need to follow them in some way. We can do this intensively while they are in pediatric care, but as they reach young adulthood, they are making a transition from pediatric care and into adulthood, going off to college and so on. So we are working on better ways to stay in touch with them online and via cell phones. That is really just starting, so we have not yet proven these methods, but we are optimistic because of how much these youth are online.

This kind of research can benefit not only HIV-infected children in the United States (of which, fortunately, there are fewer and fewer cases each year), but also the millions of children infected at the time of their birth in countries around the world where HIV/AIDS is still an epidemic. We expect that what we learn here will help design healthcare approaches and guide research in resource-poor countries like those in sub-Saharan Africa.

One of the great success stories of modern medicine is the reduction in mother-to-infant HIV infection rates, especially in the relatively resource-rich Western nations. What challenges still remain in that area?

I think there are two important challenges, one implied in the question. How do we make sure that this extremely successful intervention is accessible worldwide? We have been able to greatly increase accessibility to the medications and preventive protocols that have reduced mother-to-infant transmission, but the coverage worldwide is far from what it is here in the United States or in Europe. We know what works, but we need to make access much more widespread.

The second challenge has to do with the improved health of HIV-infected women on antiretrovirals. As a result, today we are seeing women who are actually conceiving and becoming pregnant while already on antiretroviral medication. We need to make sure that the exposure of the fetus to antiretroviral medication for the entire pregnancy is not harmful, over either the long or the short term. We have some data available, but in the past, women usually started antiretroviral medication in their second trimester. Now they are more and more often conceiving while on antiretroviral drugs. The intervention is very successful, but we don't know if it will have long-term effects.

Is your Branch supporting any new products in the research pipeline to reduce HIV transmission?

Let me make it clear here that all of this work is in close collaboration with other NIH Institutes and Centers (ICs) and other agencies. That especially pertains to new products.

One important initiative is the search for long-acting formulations for either prevention or treatment. We know that if HIV-infected people take their antiretroviral medication, they are not only healthier, but they are also less likely to transmit the infection. In other words, a long-lasting formulation that helps patients to be compliant with their antiretroviral medication regimen not only helps their health, it could also help prevent secondary transmission. So this is a really important area of research.

We also are involved in collaborative work on vaginal rings that contain specific antiretroviral medications for long-term protection of uninfected women, as well as other preventive strategies, such as using oral antiretrovirals in high-risk populations.

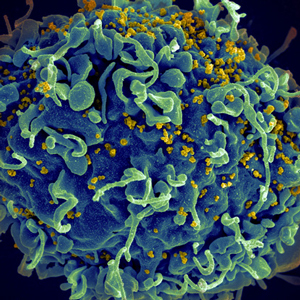

A third area of research is on monoclonal antibodies, on which we are collaborating with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Vaccine Research Center. Monoclonal antibodies are a type of protein made in the laboratory to selectively bind to a specific invader, like a virus, or to a part of a diseased cell in the body. They are already being used in cancer treatment and now researchers are studying their effectiveness for treating HIV/AIDS.

At present, all three of these research areas are being explored in clinical studies. The number of new infections is slowly going down, and we can almost guarantee that people who are infected will not transmit the virus as long as they can take and tolerate the medicine. That is why we are working on these alternative modalities. They can make it easier for patients—especially youth—to take their medications as prescribed.

Your Branch recently updated its name to focus on infectious diseases more broadly, rather than just on HIV/AIDS. How is your Branch planning to diversify its research portfolio?

What we are trying to say with the name change is that the Branch has gained valuable experience with HIV, so how can we collaborate with others, both at NIH and outside, to be sure that the best preventive and treatment regimens are available for women, pregnant women, infants, children, and adolescents? We hope to bring the same approach that we have successfully developed during our years of experience with HIV to other infectious diseases.

The NICHD's focus populations—pregnant women, infants, and children—are difficult populations to study. Our experience puts us in a position to be able to identify other major infections and to bring that same type of collaborative, clinical trial, population-based approach to those problems. This will require close collaboration with NIAID and other ICs. It is important to be sure that we are not duplicating what others are doing. We want to identify specific gaps and tackle them with new collaborations with other groups across NIH. This is a real challenge, but it's also an exciting opportunity.

One example of a specific major cause of morbidity and mortality is cytomegalovirus (CMV), which can also be passed from mother to child. CMV transmission occurs in about 1% of births, or about 40,000 births a year in the United States. Of these infants, about 10% will die or have severe problems in the neonatal period. The vast majority don't necessarily have any immediate problems, but many will have hearing loss or neurological and developmental problems later. These numbers have not changed in my 20-plus years in pediatrics, so this is an area that is ripe for the kind of collaborative approach that we have used successfully with HIV.

We can focus on pregnant women and infants and children, and it will give us an important reason to work with other groups within the NICHD. For example, there is no newborn screening test for CMV, and we have a very strong newborn screening program here at the NICHD. Neonatal CMV also causes major morbidities, including neurologic and developmental problems, another area that allows us to have strong collaborations within the Institute. With our complementary goals and strengths, we hope to have an impact on CMV similar to our success with HIV.

How can we build a CMV-free generation? Do you test women? Use newborn screening to identify infants to treat with antivirals? Do a better job of screening for other health conditions caused by CMV? There are potentially many research questions that lend themselves to this proposed expansion.

What do you see as the most promising scientific opportunities for your field in the next 10 years?

We need to finish the work that the Branch started with HIV, so much of what we need to do is about implementation. We need to make sure that there are no long-term problems related to our interventions.

This question sort of goes back to the CMV opportunity. The big challenge or opportunity is to take the model of a collaborative, population-based approach and apply it to other infections. We can start with studies here in the United States, but our ultimate goal is to package what we learn and implement it in a safe and inexpensive way in resource-limited settings.

The other major challenge and opportunity is with adolescents who have newly acquired HIV—"behaviorally acquired," as it is sometimes called. This group of adolescents is the group that has not seen a decline in the number of HIV infections. If anything, the number is increasing. Many of them are young men of color who have sex with men. They are often extremely marginalized and stigmatized, so they are a very difficult group of people to identify and engage in research.

Slowing the rate of HIV infections in this group is one of the main goals of the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN), of which the NICHD is the lead Institute and funder, although other networks are also engaged in research on this group. We have to get the number of new infections down, as we have been able to do with infants, although the approach is very different. A lot of research is on the use of oral HIV medicine to prevent infection in these high-risk youth. We have had some pilot studies among this group, but we really have to increase our focus on this problem. From a public health standpoint, it is a critical issue for this country.

Given all your responsibilities as a Branch chief, do you still find time to see patients? How does that inform your work at NIH?

In my previous work at the NCI intramural program, I was the principal investigator (PI) on a study, and I continue to follow those youth for possible long-term threats to their health. I also cared for children in Boston during my training years. Those experiences very much inform my work today. However, my contacts with my patients are now few. When I am over at NCI, I can stop by the clinic and visit with some of the patients who are still being followed because of the protocol. I have great colleagues in the program who have taken over my responsibilities as PI, and they keep me involved from a research standpoint. The people there do the clinical work and do it very well.

I still very much believe you must have good clinicians involved to have good clinical research. Clinicians bring a vital perspective, and they know what questions are really important. We work very hard to get expert clinician input into our research and to have them participate in it.

More Information

For more information about MPIDB and HIV/AIDS, select one of the following links:

- NICHD Resources

- Division of Extramural Research

- Related A–Z Topics:

- Previous NICHD Spotlights on HIV/AIDS:

- NICHD News Releases on HIV/AIDS

- NIH Office of AIDS Research

- HIVInfo.nih.gov

- AIDS.gov

Originally Posted: December 23, 2014

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP