NICHD Medical Officer Draws on Her Experience in Global Crisis

While the imminent threat of a global Ebola epidemic has faded, the impact of the outbreak in West Africa was severe, and its effects will continue to be felt for years to come. The virus ravaged communities in Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone, leaving more than 11,000 people dead.

Among the many lessons learned is the need for more research on the unique vulnerabilities of infants, children, and pregnant women during public health emergencies.

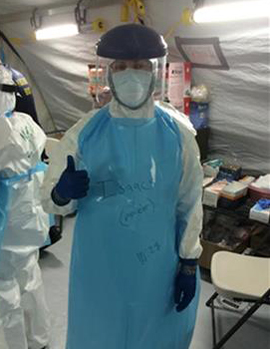

So says Lieutenant Commander Margaret Brewinski Isaacs, M.D., M.P.H., a medical officer in the NICHD Office of Global Health (OGH), who participated in the response. Dr. Brewinski Isaacs is a pediatrician and preventive medicine physician with expertise in public health, an officer in the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS), and a mother. In 2015, she was deployed to Liberia for three weeks, where she provided clinical care in the USPHS Monrovia Medical Unit (MMU), a 25-bed Ebola treatment unit that provided care for health care workers affected by Ebola. She spent an additional week in Sierra Leone, where she assisted with the investigation into Ebola infections of health care workers and provided training in infection prevention and control practices.

Supporting Vulnerable Populations

Ebola is a severe, often fatal disease with symptoms that can include fever, bleeding, severe vomiting, and diarrhea. The work of caring for patients with Ebola virus was unlike any other medical assignment Dr. Brewinski Isaacs had encountered.

“It was an overwhelmingly emotional experience to see the suffering Ebola causes,” she said. “It’s a painful and horrible disease.” As the illness progresses, the patient becomes more infectious, so health care workers cannot offer comfort by touching or holding the patient as they might in other circumstances, even when wearing protective suits. Doing so would increase the risk of disease transmission, endangering the individual provider and the team.

To complicate matters, providers were strictly limited in the time they could dedicate to patient care. Though the MMU was air conditioned, Dr. Brewinski Isaacs said, temperatures could easily rise above 100 degrees Fahrenheit inside the protective suits, posing a serious risk for heat-related illness. If a provider were to collapse from heat, the team would have to stop all other activities to remove and decontaminate their colleague, costing time and putting the entire team at higher risk.

The MMU did not have pediatric patients, but Dr. Brewinski Isaacs learned from colleagues in other hospitals and treatment units that caring for infants and children in these contexts was extremely difficult. For example, if a parent needed to be admitted to a treatment unit, it could be very challenging to find anyone to care for their children because of fear of infection. Infants and young children admitted to an Ebola treatment unit required the constant provision of basic care, such as feeding and diapering, which parents were often too sick to manage. Without supervision, toddlers could easily wander dangerously close to infectious materials or other hazards.

In addition, providers were not always experienced in pediatric care—for example, with inserting an intravenous line in children, managing their pain, or having infant formula or other pediatric supplies on hand. And with health care providers constantly rotating in and out of the treatment units, it was nearly impossible for a caregiver to stay at the bedside of pediatric patients.

Even when children survived this experience, they often had nowhere to go when discharged because their parents may have died and other family or community members may have declined to take them in.

Identifying Research Questions

Emergency health workers frequently must make on-the-spot decisions about how to handle situations like these, often with limited evidence about the best course of action.

“There are a lot of questions that research can help answer,” Dr. Brewinski Isaacs said.

How can the needs of mothers and children be woven into research protocols? If a pregnant woman with Ebola gives birth, how can health care workers achieve the best possible outcomes for mom and baby, while also minimizing their own risk of infection? Could Ebola survivors in a treatment unit safely help care for children who have no other caregiver? These are some of the questions research has yet to answer.

Since joining NICHD’s Office of Global Health, Dr. Brewinski Isaacs has worked to disseminate the clinical observations she made while on deployment to researchers and clinicians working in public health. She also has contributed to interagency discussions on Ebola response efforts and their implications for future infectious disease outbreaks.

As for her deployment to West Africa, she feels grateful for having had the opportunity to serve.

“I really saw it as why I became a doctor, to contribute what I can in a public health emergency,” she said. “I was extremely grateful for the support of my family, co-workers, and fellow USPHS officers. It was an honor and a privilege to be able to support the response efforts.”

More Information from NICHD

- A-Z Health and Research Topics

- Office of the Director (OD)

- Past Features on Global Health

Originally Posted: April 4, 2016

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP