NIH Consensus Development Conference on Rehabilitation of Persons with Traumatic Brain Injury

Appendix A

*Paper commissioned by the Panel.

The Consumer Perspective on Existing Models of Rehabilitation

for Traumatic Brain Injury*

Theresa M. Rankin

INTRODUCTION

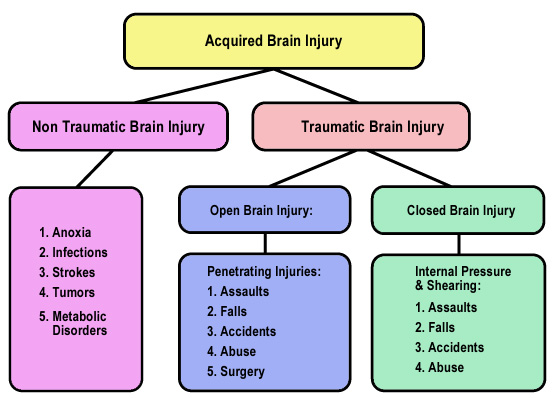

This Consumer Perspective report is a discovery project for the purpose of identifying themes and trends in the consumer literature on views and needs of consumers on traumatic brain injury (TBI) rehabilitation (see Acquired Brain Injury, Figure 1, Lucas, 1994). A consumer is defined as a person with a TBI or a family member. The literature review was guided by a set of questions presented by the NIH TBI Consensus panel that address (a) the current rehabilitation models and (b) the various practices/methods of treatment for traumatic brain injury. The questions used were:

- What were perceived as the most effective rehabilitation practices resulting in integration back to the family, community, and work/schools for individuals with TBI?

- What were perceived as the least effective rehabilitation practices for individuals with TBI?

- Were the goals of rehabilitation for persons with TBI established by the consumers, the family members, the clinicians or a combination?

- Were the goals perceived as satisfactory by consumers?

- Are there recurring themes about the goals, organization, or administration of TBI rehabilitation that are perceived to be overlooked by the scientific and/or medical community?

This discovery project serves to acknowledge the consumer perspective on a multiplicity of issues regarding TBI rehabilitation, but it is not designed to provide systematically collected data of what actually works in TBI rehabilitation practices. Based on the literature review consumer recommendations for research will be discussed in the Summary.

METHODOLOGY

In an effort to identify nationally published sources of literature that originated with or reflected consumer perspectives, the leading authorities in the field of brain injury were contacted. The inquiry for consumer literature on rehabilitation practices found reports primarily from researchers or therapists speaking for or about consumers. The national project directors and resource managers acknowledged that no compendium of consumer literature exists nor is there a focused literature analysis dealing with a scientific/medical model review.

Therefore, the scope of this consumer-driven and consumer-oriented project, conducted over a period of four months, involved developing a search strategy focused on locating the networks of consumers who self-publish and for consumers who contribute to the national and regional publications. The literature that was reviewed included 107 sources with approximately 1300 items that were collected from the following sources:

- The Brain Injury Association (BIA) library

- Newsletters of independent foundations and a collection of publications from the 42 BIA State offices,

- Randomly selected personal accounts in books, national disability magazines and grant publications

- Consumer retrospective survey articles for TBI/disability projects

- Consumer perspectives and advocacy statements from the National Brain Injury Conference, 1994 OSERS

- Websites related to disability/TBI

- Presentations from national/regional conferences

- The 1992 Congressional Testimony on TBI Rehabilitation

- Paralyzed Veterans of America, National Office

- NARIC, Nat'l Rehabilitation Information Center

The results of the consumer perspective literature review provided first person accounts on the wide range of needs and concerns; this broad overlay of topics was used to identify themes and trends primarily in the principles and practice of rehabilitation for community reintegration. The literature relevant to each consumer question on community integration is presented in terms of (a) issues as summarized from the consumer literature, and (b) consumer statements illustrating the issues.

PERSPECTIVES OF PERSONS WITH TBI and THEIR FAMILIES

Question 1: What were perceived as the most effective rehabilitation practices resulting in integration back to the family, community, and work/schools for individuals with TBI?

Consumers, recovering from TBI diagnosed as mild, moderate or severe, tended to perceive the most effective rehabilitation practices for community integration as those that focused on person centered planning and enhancing the quality of their life: physical well being, mental health, return to school or employment, and community living.

"There is much to say about Acquired and Traumatic Brain Injury. The needs of the Acquired and Traumatic Brain Injured individual are broad and significant. There is a void in the health care for these people that must be addressed. How that will be accomplished is more dependent on the funds that are available than upon the techniques or facilities that are provided" (Fogel 1998).

"All too often, we define outcome in terms of medical prognosis, family wishes or monetary availability. Hopefully the TBI Act of 1996 will offer the monetary support for rehabilitation efforts to become more community-oriented and less institutional in nature." (Cleveland, 1997)

"We must recognize all resources for us to use in 'living our own recovery,' thus allowing us to have lives, not outcomes. Total healing, recovery and good health may need to involve the use of concepts, techniques and resources outside of the box of traditional medical/drug models." (Cannon, 1994)

The primary issues related to satisfaction with quality of life for a person with TBI are acknowledged in a current community integration outcomes study with 300 consumers (Bogner, 1995):

- The ability to be healthy & free of medical problems

- The ability to live independently

- The ability to achieve and maintain financial stability

- The ability to lead a productive life

- The ability to feel integrated into a social community.

To understand the course and potential barriers to optimal recovery, the outcomes study, selected these several areas of outcome based on recommendations from consumers and family members seen as affecting long-term quality of life. General satisfaction with one's life situation is being studied extensively (see Gordon, 1998).

The most effective rehabilitation component from the family perspective is identified as education, support services and family systems therapy:

Anne E. Peterson, M.S., has worked over 10 years in health care and clinical research, and is a family member of two brothers who sustained TBI, Hugh in 1972 and then Peter in 1995: "It wasn't just the medical advances of 23 years that gave Peter a better outcome, and it certainly wasn't better insurance coverage. The change was the leap in awareness of what it takes to adjust and live with a brain injury for life. Through new rehabilitation methods that included lifetime family support therapy, my brother and his wife learned to better use their own resources to recognize and respond in healthier ways to the changes that naturally occur. As a result, Peter's family has survived." (Peterson, 1995)

These quality of life issues are identified by consumer authors who have 10-20 years of first person knowledge and systems expertise in surviving the challenges of TBI and rehabilitation.

Lynda G. Cleveland, doctoral candidate University of Texas at Austin, a person with TBI sustained in 1984; after being told "you'll never work again" she recalls years of agonizing physical therapy and the years of living the 'silent epidemic':

"You can begin to sense inadequacies in our rehabilitation systems that fail to teach compensatory strategies for life beyond brain injury, and you certainly see the problems with the traditional system of belief that after 18 months surely the individual has made all the progress really possible.

I believe there are three keys to outcome potential in 'my story' that can benefit survivors of all ages:

- Future Time Perspective: Regardless of whether the individual's picture of the future is correct or incorrect, this picture deeply affects the mood and actions of the individual. We should encourage each survivor to verbalize his/her personal vision of their future, and let them work towards it. So what if the goal seems medically unattainable to us, if it keeps the survivor working towards improvement, we have accomplished a major task in rehabilitation--hope.

- Zone of Proximal Development: This concept of Vygotsky (1978) represents the notion that instruction should be designed just beyond the student's current level of development, not too difficult or too easy for the student.

- Flow: Csikszentmihalyi (1990) describes flow as a process of achieving happiness by gaining control over one's own inner consciousness. If we can assist our clients in finding this control, their outcome potential increases." (Cleveland, 1997)

Question 2: What were perceived as the least effective rehabilitation practices for individuals with TBI?

Consumers tend to perceive the least effective rehabilitation practices as those that do not address the systems issues of the TBI and long term real world functional issues. The systems-focused rehabilitation model focuses on coordinating rehabilitation services within a lifelong continuum of care in order to understand all dimensions of an injury and the discovery of real-world patterns of function (Dolen, 1991).

With the current medical model, consumers report these areas of concern:

(a) the under/misdiagnosis of TBI

(b) inappropriate diagnosis and placement

(c) failure to provide person centered supports for related problems:

- substance abuse treatment

- sexuality: adapting to disability

- psychiatric: neurologic impairment

(d) difficult access to long-term rehabilitation & case management

(e) cultural diversity and cultural healing belief systems

Examples from the literature that reflect the least effective rehabilitation practices are:

(a) the under/misdiagnosis of TBI

The medical model addresses the physical injuries, but the family finds itself searching for brain injury diagnosis and rehabilitation:

Diane Murphy, a survivor since 1990: "I am six years post-accident. However, getting here was not an easy task. Taking the advice of very educated Dr.s, my husband brought my broken body home after being in the hospital in critical condition for two weeks. My family did not worry about my brain injury, at least not out loud. They tended to the visible injuries thanking God every day that my daughter and I had survived the accident. Who ever heard of a brain injury that doesn't kill the person or put them into a life-long coma? Right?

Becoming better wasn't nearly as hard as finding the right place to get better. I would really like to see the health community and the general population informed about all the problems associated with a mild brain injury. I am hoping that the next person with a brain injury gets directed to immediate care, not a band-aid excuse of 'Don't worry - it will all work itself out'." (Murphy, 1996).

The medical model provides a narrow window of entry for the majority of the identified TBI population who are seen in ER, but the protocol for diagnosis and referral is neither clear nor guaranteed:

Dr. Claudia Osborn, July 1988, injured as a bicyclist, taken to ER, but discharged within several hours. The at-home observation by her friend, Dr. Marcia Baker, was reported to Osborn's mother I can tell you I was terrified about brain damage, but she woke up. She seems just fine, just fine.

In March 1989, unable to return to her medical practice, cognitive rehabilitation services were secured by Dr. Osborn not in her community in Michigan, but at New York University's Head Trauma Program.

Osborn's observation in correspondence to a member of the rehabilitation team in 1990 after rehabilitation: "I know I'm lucky. After all, I have a happy job, it looks as though I will be teaching, my writing is progressing well, and I still make my home with Marcia. Even so, Joan, despite my blessings, despite rehabilitation, I find my life difficult. How much harder it must be for the others."

"If I had been younger at the time of my injury, without long-term, strong relationships with supportive people; if I had lacked vocational ideas and life experiences; if I'd had greater impairments, I doubt that I would be okay." (Osborn, 1998)

(b) Inappropriate diagnosis and placement

The existing health care delivery system provides no choices or options for the services that people really need to address areas of dual diagnosis (substance abuse, mental health, TBI & spinal cord injury), as well as the areas of chronic illness, depression, or chronic pain.

Constance Miller, M.A., Director of the Phoenix Project, sustained a TBI in 1982: "'The System May Get You'. Treatment for the sequelae of closed head injury is frequently colored by the presence of an unseen, third party. In a number of circumstances, the type as well as the length of treatment is decided by individuals outside of the actual treatment situation. Too frequently, the uninformed medical or psychiatric professional called upon to provide services forms an inaccurate diagnosis. This diagnosis can lead to inappropriate treatment and rehabilitation plans." (Miller, 1988)

The constant battle for consumers is not only to access health care but to navigate the obstacles in the managed care system as well as disability barriers to achieving one's goals.

Tony Lazzaretti identifies the critical need to make appropriate services available: "I was injured in 1983; from July 85 to Dec 85, I participated in a hospital that served people with psychological problems. This was the only treatment setting that my insurance company would approve, but it was also the only opportunity for professional support at the time, so I took it. While I was in the hospital I began to see that my problems were not psychologically-based, they were the result of the problems caused by my brain injury. This was not understood by the hospital staff and I felt trapped and scared."

In June 1986, TBI rehabilitation began and "dealing with the problems caused by my brain injury was not necessarily easier, but I did feel more calm because I could explore the injury with other survivors and with professionals. I felt less isolated and less trapped." (Lazzaretti, 1993)

(c) failure to provide person centered resources/services for related problems

The physical, cognitive, psychosocial, behavioral services that a person needs after becoming medically stable continue to be limited in scope. Additionally, the current rehabilitation models need to prepare the consumer and family for assuming a management role in securing specialized treatment and needed services.

As a college graduate, a young man moved to California and a new job. "P.S." was injured in 1988 as an alcohol impaired driver. He describes the limited rehabilitation and long search for treatment after the single vehicle car crash: "My rehabilitation started immediately after I awoke from the coma. I went to one of the top rehabilitation centers in California but they failed to hold out some hope to me of ever walking again. I believed them and sat around for almost 3 months, not even trying.

Due to the diagnosis I received and the probability of never walking again, I lost all hope of ever returning to 'normal.'

I was faced with the decisions to either die miserably or to get on with my life. I chose the latter. After I joined that twelve step group in New Jersey, I found that I wasn't alone and was among people that understood. Since the accident changed my life and through the process of self-discovery, I have felt drawn to counseling field and I'm now pursuing my Master's Degree in Substance Abuse Counseling." (TPN Magazine, 1996)

The TBI rehabilitation programs also need to address the day to day life management issue of relationships and rebuilding the quality of emotional intimacy. Sexuality and the adjustment to disability after TBI are becoming integrated into the rehabilitation process, but the teaching of communication and interpersonal boundaries are elements that few programs address. "If the practice of rehabilitation is to move beyond simple physical and functional restoration to genuine healing and restoration of quality of life, more time, energy and imagination must be applied to helping restore such qualities as intimacy, communication and spirituality in persons with brain injury and their families." (Blackerby, 1993)

Carol Taylor, now on a new career as a Paralegal, sustained a brain injury caused by a driver who ran a red light:

"'Was I Absent the Day They Covered This In Rehab?' The ability to meet people decreases for a survivor specially if you've lost the ability to return to work. For the first couple of years you're busy "pursuing" just getting your life back on track. How does one pursue a relationship when they have limited physical abilities?" (Taylor, 1993)

Of equal importance in rebuilding one's life is the counseling and intervention in the domain of mental health.

Frank Foss, a musician who studied at the Royal Academy of Music, sustained a TBI that detoured his goal to be a College Level Music Teacher: "I ended up homeless on the beach, very disoriented. I found myself cooking outside, surrounded by strangers. I had no security and felt psychologically disturbed from emotional issues." (Vincent 1998)

The intervention was provided by his parents, Bill and Lita Manson: "My parents brought me to a Psychiatrist. Dr. Robertson pinpointed neurological damage after a CAT Scan. Because of his professional attention and some cognitive rehabilitation, I graduated from college after my injury. Now I am able to work again. Some of us, who are just a little out of the ordinary because of TBI don't need institutionalization. It is very difficult to not feel a part of society. We do need to feel that we exist in a community that accepts us (Vincent, 1998).

The family perspective by Lita Manson: "At times, I am bitter, I was quite shocked by the unkindness of people here in the USA who need us all to be 'beautiful people'. I know from my travels abroad as a Social Field Anthropologist, that brain injury can result from many causes and can happen to anyone. This is a silent epidemic! Brain injury must be studied. The American Public needs to be awakened about TBI." (Vincent, 1998)

(d) difficult access to community based long-term rehabilitation & case management

The rehabilitation models provide no follow-up plans, so that after the families' resources are exhausted, the threat of institutionalization is predominant.

John Burns sustained a TBI at age 21 in Ohio: "After the car accident and treatment in the hospital, I began a ten year battle to regain my rights and my dignity. I was transferred from nursing home to nursing home trying to find someone who cared enough to ask me if I needed anything, instead of telling me what I needed or worse, ignoring my simple questions.

I now live in a home in a community setting, with another man who also has a brain injury. We have staff in our home 24 hours a day who address our physical needs, our emotional needs and are also our friends." (Life After Brain Injury, 1994)

A primary theme in the literature from family members, significant others, and caregivers is the compounded crisis and trauma of fighting for appropriate care:

Janet Rife, parent, author and disability advocate, fought the crisis for her son, Brian Rife, injured in 1985: "Considering how hard we had to fight for funding and continued therapy when Brian's future hung in the balance, it is easy to imagine how many people have neither the energy nor the knowledge to stand up to insensitive systems.

Using sophisticated medical technology to save a life, and then consigning that person prematurely to maintenance care is a horrendous injustice." (Rife, 1994)

(e) cultural diversity and cultural healing belief systems

Health care providers need to understand the belief systems embodied by the people coming in for diagnosis and treatment. This is an area of study that the literature is lacking in, but is an area of concern surfacing at national and regional conferences. "The United States is represented by many diverse populations. However, there is a subset of this multicultural society which utilizes fewer health services and collectively tends to be in poorer health. This subset is predominated by African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, and Asian/Pacific Americans" (Morgan, 1997). The need to bridge the gaps in health care and injury prevention are paramount in alcoholism, unintentional injury, depression and violence related injuries.

Advocate's Perspective: "My name is Theanvy Kuoch and I am a survivor of the Pol Pot Regime in Cambodia. I am a Health Program Assistant for the State of Connecticut and am also a Family Therapist. I am here today to share with you about the culture and context of the Cambodian people and how it affects their health care. In the Cambodian culture, if you don't feel good, something is wrong and there is always something you can do about it. Sometimes you do something traditional like coining, sometimes something spiritual or sometimes something Western, like surgery or medicine.

If you feel that a Cambodian does not have a condition that you can treat, suggest that they seek help from a Cambodian healer or a monk if they are Buddhist. But, tell them clearly that you cannot help with this illness; don't tell them they are not sick." (Kuoch, 1997)

Question 3: Were the goals of rehabilitation for persons with TBI established by the consumers, the family members, the clinicians or a combination?

Based on this literature review, consumers report varied experiences with involvement in goal setting during rehabilitation. This question assumes that consumers have the access and the availability of their families as well as the length-of-stay allowance for goal setting provided under full comprehensive insurance coverage or long term case management. The reality for consumers is that the doorway for goal setting is set by hours or days, not long term outcomes of skills, strength or self-esteem.

Consumers present their perspectives in terms of recovery, not rehabilitation, this being a long-term outcome process which is not complete until restoration of quality of life is established and maintained. Therefore, an important "discovery" of this paper is to recognize that different languages are being spoken in reference to goals by the medical/scientific community compared to the language of consumers and families. Consumers face an ongoing search for access to systems and appropriate services when talking about "rehabilitation goals."

Kathy Moeller is a skills trainer and creator of the Brain Book@ Life Management System; a compensatory skill and residual strength building program for persons with brain injury. Kathy experienced a brain injury in 1990, but received appropriate acute care, 5 months in residential program therapy and 9 months of outpatient treatment to in which she learned how to apply new life skills to a professional environment. In her 1994 first published article post trauma, "Compensatory Skills Training," she states:

I am passionate about the value of practical compensatory skills training because solid strategies are essential for people with head injury to succeed at work. Many of my peers would be working, too, if they were given the opportunity to learn how to compensate. The main difference between my situation and the situations of many of my clients is that many of the individuals with whom, I work enter the vocational rehabilitation process without receiving much in the way of compensatory skills training. Based on the so called "medical model," many people with head injury are discharged from acute care, deemed medically stable and ready to return to their homes and families--with little or no cognitive rehabilitation therapy.

It saddens me to encounter people exactly like myself who receive little or no follow-up care for practical compensatory skills development. Often, they do not realize that they are lacking in this area. What they do know is that things are not working right, they are hurting, and they need 'something', not quite knowing what that 'something' is." (Moeller, 1994)

Consumers have long known that the process of brain injury recovery does not follow a linear path once one has exited the acute phase of medical care. In the same way, services designed and driven by consumers acknowledge that the individual needs of consumers are different in substance and in timing. "Providing the service that the individual needs at the appropriate time in the recovery process is the most effective, and empowering rehabilitation practice." (Cannon, 1994) The universal goal is to have all consumers experience the following:

Tony Lazzaretti's perspective and experience from a specialized brain injury rehabilitation program: "I had supportive opportunities to work collaboratively with therapists out in the real world. These initiatives were focused on goals that I identified as being important to my future. Rehabilitation gave me a foundation to move forward with my life." (Lazzaretti, 1993)

Question 4: Were the goals perceived as satisfactory by consumers?

Overall, consumers report dissatisfaction with the outcomes of TBI rehabilitation based on not being included in the goal setting and the common problems of the lack of information (Dolen, 1991), the lack of options, the lack of assistance for problem solving and decision making, and lack of coordination among programs and service providers (Palmer,1998; Taylor,1998; Vincent,1998). A characteristic of the consumer literature is the retrospective value that consumers' have given the inappropriate length of time between when the consumer experienced TBI, the access to appropriate rehabilitation, and a return to the community, and the window of opportunity for when a consumer finds the means by which to publish a viewpoint.

The goal setting process in any one quality of life domain may not even begin until several years of survival have passed and the consumer discovers a new resource or community of support. The profile of persons with TBI includes a population of survivors who are just now being acknowledged but still not accessing critical services after years of survival: "(1) individuals with cognitive impairment who 'lack physical disabilities'; (2) individuals without an effective advocate to negotiate the social service systems or without a social support system; and (3) individuals with problematic behaviors….without treatment, these individuals are most likely to become homeless, institutionalized in a mental facility, or imprisoned." (GAO/HEHS-98-55, 1998)

Yet there is also a population of survivors, now in their second or third decade of life post trauma, who are working on the issues of aging and living with this chronic disability:

Kiersten Rain sustained a TBI as the result of a violent sexual assault nearly two decades ago:

"Two weeks after the attack, as I slowly gained consciousness, I began to discover that the world had changed, irreversibly. All decisions were made for me. My own opinion no longer counted. When I lost the ability to speak, I lost the ability to make choices concerning my life. When I was eventually told I suffered a severe brain injury, I thought that meant I was mentally retarded. Other's responses to me only validated this.

As years moved on, I re-learned many things. ….A kind neurologist told me that even though my body was filled with uncontrollable and painful spasms, he could see that I still had a mind.

A few years ago, I heard about the Mt. Sinai Medical Center's research concerning women with TBI. ....For the first time in over 15 years I was in a group of others who could truly understand me. These women shared with me the same type of struggles to survive and function with their disabilities." (Rain, 1997)

The often unspoken and undiagnosed pervasiveness of secondary conditions includes chronic orthopaedic or myofascial pain, chronic fatigue, vestibular complaints, fibromyalgia, post-traumatic vision syndrome, immunosuppressive disorders, neuroendocrine dysfunction, and neurological difficulties (Hibbard, et al. 1998).

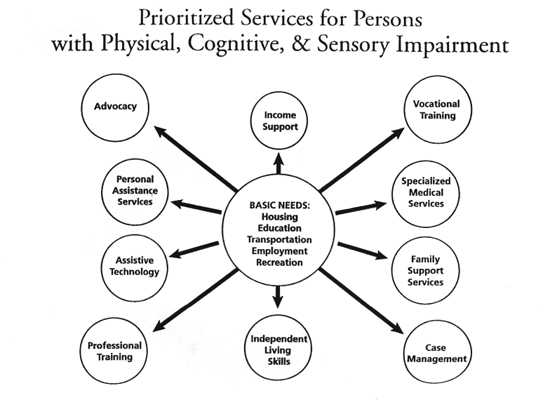

The consumer dissatisfaction and decades of concerns are again based on issues dealing with community integration and the larger quality of life questions cited in Figure 2, Advocacy Statements of Consumers (Life After Brain Injury: Answers I Can Live With (1994), and Figure 3 the "Community Integration: Barriers to Optimal Quality of Life" provided by Corrigan (1994). The reality for consumers is that the medical model of rehabilitation may adequately address goals in physical survival, but the remainder of rehabilitation models in cognition, psychosocial, behavioral and vocational domains are currently not successful in addressing long term consumer and family needs for education in the transitions needed for 'recovery beyond rehabilitation' (Patrick, 1996).

Question 5. Are there recurring themes about the goals, organization, or administration of TBI rehabilitation that are perceived to be overlooked by the scientific and/or medical community?

According to consumers, the primary missing piece in the goals, administration and overall organization of TBI rehabilitation is the active involvement and consideration of the consumer perspective. This paper acknowledges the framework of a universal consumer perspective presented in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, a model of the community integration components (State of Virginia, 1994). These three illustrations of the consumer perspective serve as essential elements that must be considered in the design and data collection protocols for future studies and designs of effective systems for rehabilitation of people with TBI.

These three elements have been introduced in different arenas of TBI rehabilitation design: a national consumers conference, a Rehabilitation Services Administration Comprehensive TBI Center now a TBI Model System, the State of Virginia and the MidAtlantic TBI Consortium. And all of these 'voices' speak to the long overdue change in expectations, practices, and policies supporting self sufficiency and community membership. This literature represents how persons with TBI and their families are acquiring piece by piece, ownership of the rehabilitation process and regaining the array of rights that are infringed on after a catastrophic injury.

"…..as the community integration and independent living movements being to converge.....there is an evident shift in practice and policy from defining community life in terms of residential facilities toward more flexible, consumer-responsive approaches. Yet, in part due to their medical roots, fields such as traumatic brain injury are just experiencing these changed expectations, practices and policies supporting self-sufficiency and community membership on the part of people with disabilities" (Racino & Williams, 1994).

Poor outcomes in rehabilitation for brain injury survivors may be directly related to failure to involve consumers in goal setting; failure to consider long term quality of life issues in planning rehabilitation; failure to appropriately diagnoses and provide treatment for persons with TBI in programs that will maximize their residual strengths. In addition to these problems within the existing rehabilitation models, persons with brain injury typically find themselves with no supports after the initial period of acute or post acute rehabilitation (Windsor, 1993a).

Wanda Windsor, Project LINCS Director, San Diego Community College District (SDCCD) and a person with TBI, stated during her presentation at the Journey Toward Independence conference, 1993:

"at a time when funding resources are scarce and long term needs of survivors are expensive, it is incumbent on providers and community support systems to design creative coalitions and partnerships that meet the needs of individuals with head injuries, most of whom are without long term insurance support for rehabilitation, re-education, and community re-integration (Windsor, 1993a)."

CONCLUSION: THE CONSUMER PERSPECTIVE ON TBI REHABILITATION

An important acknowledgment throughout this project is the difference in language and focus presented in the consumer literature compared to the medical/scientific literature. The medical community speaks of models and modalities, the consumer speaks of the return to their community and the relationships that signify their quality of life.

The gaps in the current "continuum of care" challenge the consumer to create pathways for getting on with life in spite of it all (Nelson, 1990; Gwin, 1992; Bogdan, 1992; The Needs Conference, 1994). Access to wellness is one of the predominant themes of consumer literature that represents a gap in the continuum. The consumer, the majority relying on state assisted services and a small percentage enabled through insurance or personal funding, is characteristically searching for access to appropriate health care (Vincent, 1998), individual and family therapy (Rocchio, 1998), complementary medicine (Dolen, in press), educational resources (Windsor, 1993a), and support services for independent living (Gwin, 1992) and vocational development (Thomas, 1993).

"Fourteen years post injury, I finally realized that I couldn't do everything I wanted. I became clinically depressed and began to grieve the loss of a life I could never have. I sought the help of the Michigan Rehabilitation Services. The head injury specialist there sent me to my first head injury rehabilitation program in 1989. Today I am working in my chosen field of interest (Social Work). My greatest strengths lie in group work. I have created an acceptance group for head injured survivors, where attitudes and skills necessary for successful independent living are developed" (Bauser, 1993).

Addressing this loss of self and the grieving process is an area of rehabilitation often overlooked or only partially included in the process of cognitive rehabilitation. But given the fragmented system of care, most consumers and families need to be linked with the existing network of community based brain injury support groups and other self-help groups (Rocchio, 1998).

Another critical recovery and systems need deals with the principles of self-determination and independent living as outlined by consumers in The Needs Conference for Underserved Consumers with Head Injury (1994), Life After Brain Injury: Answers I Can Live With (1994) and in Navigating the Future (1994). These first-person accounts demonstrate that the knowledge and expertise of the consumer provides a critical resource for structuring rehabilitation practices and community based services (Youngbauer et al., 1994).

In terms of the organization of rehabilitation, the current rehabilitation model continues to provide access to acute rehabilitation, but with an increasingly shortened approach to care. Consumers and their communities are fully aware that this model is not adequate in designing or achieving long term effective outcomes in physical, cognitive and psychosocial function.

The models for effective involvement of consumers begin with a TBI Curriculum for consumers and families to navigate the stages of trauma, rehabilitation and recovery (Dolen, in press; Miller, 1988; Rife, 1994; Talbert, 1991). The primary and secondary disabilities present a long term cycle of searching for information and referral (I&R) (Rocchio, 1996a). The point of entry for a consumer into this I & R process begins from time of injury, to the ER and Trauma Center, throughout acute and post-acute rehabilitation, and continuing for the community integration/quality of life (Brain Injury Association of Virginia, 1994).

Isolation is a chronic systems condition that impacts the family and consumer: " I am a believer that the entire family unit should be rehabilitated. When the family is a part of the rehabilitation team it is more likely that the family will not become dysfunctional " (Bolden, 1992).

Of equal importance to the quality of life for persons with TBI is employment. As known by James S. Brady, Chairperson of the Board of Directors of the Brain Injury Association: "The most common question among those with TBI is 'When will I be able to return to work?' Society is such that often our sense of worth is directly related to our occupation. Nothing can destroy self-esteem faster than having your opportunity to 'make a living' taken away.

The only thing we want or deserve is to have the exposure and access to all the community has to offer. We are entitled to be treated with the same dignity and respect afforded non-disabled citizens.....and the chance to experience the benefits of employment that most of the workforce takes for granted: a regular paycheck, an avenue for developing friendships and the opportunity to be seen by others as a valued, productive member of the community" (Brady, 1994).

Summary and Recommendations:

In 1992, consumers testified to a Congressional Subcommittee about their dissatisfaction with the existing facilities and models for rehabilitation.

"I am alarmed at the lack of consumer involvement in services for people with head injuries, the lack of community based supports, and alternatives to institutionalization. The Federal Government continues to fund multimillion dollar research grants that do not address our real needs. Tax dollars would be better spent on identifying and developing community-based supports. In the current rehabilitation system, there is this continuum of care with the difference being that you move away from your community and support the facility's community" (Watson, 1992).

Given the fundamental changes in the health care environment, including the shift from inpatient to outpatient care, the need for community based research and innovations in rehabilitation models is evident.

Based on the review of the available literature here are recommendations for research:

- Consumers know first hand that there are no existing "seamless or wrap around" rehabilitation systems. Even where a consumer receives effective medical rehabilitation, the certainty of appropriate cognitive or behavioral rehabilitation may not be readily available or accessible. RECOMMENDATION: Establish research on consumer and family well-being in longitudinal studies to track the progress of people with TBI throughout the course of specific rehabilitation processes and then beyond to assess family and community integration. The need to address the complex clinical sequelae within a lifelong continuum of care is a discovery project for a collaborative research panel.

- The core of the innovative rehabilitation model, involves the self-advocacy frameworks needed for acquiring the systems skills and individual life skills to continue the recovery process. RECOMMENDATION: Conduct community based studies of the consumer driven paradigm shift. Examples of innovative models include the Project LINCs --- "the least expensive cooperative continuum of community reintegration services for persons with brain injuries" (Windsor, 1993b) implemented through the San Diego Community College District and then in partnership with the San Diego Brain Injury Foundation; the Participant Action Research model at the RTC of Mt. Sinai Medical Center, New York City (Campbell-Korves, 1995; TBI Consumer Report #1, 1998); and the Head Coach Peer Support/TBI Curriculum component to educate and empower the consumer (Brain Injury Association of Virginia, 1994).

- This consumer project demonstrates a need for not only compiling consumer perspectives throughout the continuum, but also establishing a protocol for researchers/clinicians to integrate the anecdotal and qualitative information into current literature and the design of future research studies. RECOMMENDATION: Establish a qualitative research project for the analysis of themes and trends in consumer literature to be conducted as a collaborative design by consumers and researchers. This project has a ready Website network (Miller, 1988; Moeller, 1998; Palmer, 1998; Taylor, 1998; Vincent, 1998) capable of such a national endeavor to create the template for accessing and analyzing such information. The collaborative inclusion of the consumer perspective in publications (Corthell, 1990; Durgin, 1993) does introduce the use of first person accounts, and is the start of comprehensively addressing the research needed to increase the translation of clinical theory to community practice.

- Best of Practice in Neuropsychology: RECOMMENDATION: There is a need to encourage the further development of ecological neuropsychological profiles for determining functional analysis and continuum/intervention support services. With few exceptions, the literature illustrates a pattern in which service providers in the current medical and rehabilitation models profile an individual in a limited setting and then select treatments without providing a coherent rationale by which such selections are justified.

- 5. Best of Practice in Person Centered Planning: The consumer lay literature demonstrates that approaches directly tied to holistic and person centered planning are investments in long term favorable outcomes. RECOMMENDATION: Research is needed to describe how the areas of an individuals well-being, health, personal safety, personal development, vocational/educational and community/relationship involvement are affected by TBI. "The consumer and community emphasize the collaborative roles in person centered planning to achieving cost effective outcomes for independent living and community integration by addressing the specific environmental variables impacting a consumer's lifestyle" (Windsor, 1993b).

- Psychosocial Outcomes Research: RECOMMENDATION: Consumer Driven Psychosocial Needs Assessment. The scientific community acknowledges that "psychosocial outcomes researchers have often given little weight to information provided by persons with TBI. Instead they have given preferential treatment to information provided by relatives. Reports of reduced cognitive capacity and impaired self-awareness have served to diminish the credibility of self-reported outcome information. Despite generalizations about impaired awareness, there is little research to support the notion that family members provide more accurate information about every aspect of outcome." (Sander, et. al, 1997)

- Complementary Therapy: Consumers cite the value of combining several positive therapeutic approaches in order to achieve a manageable state of health (Dolen, in press; Vincent, 1998). Individuals and families seek beyond the traditional and accepted medical therapies, pursuing all options "to promote an optimal outcome" (Rocchio, 1996b). To date, the investigation for the mainstreaming of complementary medicine has been in isolation compared to the pharmacological applications that the medical model relies on in addressing the chronic or secondary conditions resulting from traumatic brain injury. RECOMMENDATIONS: based on the consumer literature the following areas of interest in complementary medicine and treatment are identified: Pain Management (CranioSacral Therapy), Nutrition (Antioxidants), Sleep Disorders, Chronic Fatigue, Neuromuscular Exercise (Feldenkrais Therapy), Grief and Healing, Stress Management (Hypnotherapy), Depression, Spirituality and Healing. At this time, the Office of Alternative Medicine at NIH has information on three TBI Research Grants: Homeopathic Treatment of Mild TBI; EEG Normalization Therapy for Mild Head Trauma; Music Therapy and Brain Injury (Office of Alternative Medicine, 1998).

- The Continuum of Care - "Navigating the Future" (Figure 5): RECOMMENDATION: The existing rehabilitation model needs to reconfigure from the linear design, where the family and consumer are without ownership, to a Continuum Model where there can be increased reliability that even when treatment ends, there is access to education and needed therapy. The current rehabilitation paradigm perpetuates a cycle of crises with early patient discharge. For individuals, families, and advocates this is difficult to master as they lack "systems skills" by which to identify short or long term bridges for problem solving.

- RECOMMENDATION: The current research models also need to be reconfigured to acknowledge the critical component of consumer driven Participant Action Research. Established in 1993 at the Mt. Sinai Medical Center in New York, PAR integrates people with TBI and their significant others directly into all aspects of a program of action-oriented research. (Campbell-Korves, 1995: TBI Consumer Report #1, 1998)

- RECOMMENDATION: A national writers conference at NIH would bring together the network of consumers, educators, researchers who are involved in TBI rehabilitation. This conference could build on the network created out of Live After Brain Injury: Answers I Can Live With, the 1994 OSERS National Brain Injury Conference. Consumers, the medical community and scientific researchers could discuss collaborative efforts to author educational materials on TBI Rehabilitation and Community Reintegration. This identifiable network is accessible through the Brain Injury Association, the National Association of State Head Injury Administrators (NASHIA) and complemented by the new TBI Advisory Councils required by the TBI State Demonstration Grants funded through the TBI Act of 1996.

- RECOMMENDATION: Specific Rehabilitation Models for further research:

- Ecological/Educational Rehabilitation Practices

The process of re-learning is critical to successful integration back into the family, community and work/school. This process is more effectively facilitated when learning takes place in natural settings, in addition to the classroom or rehabilitation setting. Project LINCS (Learning in Natural Community Settings) was designed to provide follow-up with the real life needs of survivors and their families. This model views the rehabilitation process "as essentially educational, requiring skilled instructional training and long-term maintenance support in community settings....The goal of Project LINCS was to establish a consumer-driven system to engender successful long-term employment or productive activity, maximize independent living and provide community support to survivors and families. The intent was to do these things through a cost-effective community-based reintegration program for adults with head injuries, funded by partnership coalitions and cooperative agreements within a network of providers and consumers that would be replicable in other communities nationwide" (Windsor, 1993b).

- Consumer-Directed Rehabilitation Practices

A program utilizing rehabilitation in neuro-behavioral training is the club house model, providing a consumer-driven environment where individuals are "members" rather than "patients". In the process of running the clubhouse, the members learn life skills that enable those considered "too disabled" to gain greater control of their lives. This provides a safe, supportive environment where individuals can begin to explore the question, "What next?" (Jacobs and DeMello, 1995). The process of community rehabilitation is to achieve or regain the confidence and skills necessary to lead vocationally productive and socially satisfying lives (Rufing, 1995)

. - Empowering Persons with TBI for re-entry to the world of work.

With the goal of providing better outcomes in the delivery of employment services, Project CIRCLE established a new collaboration among service providers under the guidance of ICON Community Services (Yaffe, 1993). The project combined the consumer's determination and willingness with the at least three service providers: the case management services of a community based agency, the resourcefulness of the vocational counselors from the Department of Rehabilitation for the state (MD,VA,DC) and the creativity of the employment specialist in developing work re-entry strategies.

Project CIRCLE is based on collaborating with metropolitan area businesses which have agreed to provided a Mentor to the new employee. The Project CIRCLE staff identifies the job tasks that match the skills of the client, and then provides training and support during this "situational assessment." The focus on empowering the consumer involves first building a "circle of support", which is a core group of persons close to the individual who can provide hope, encouragement, and advice as the work re-entry process is carried through for a successful return to the world of self-sufficiency and community membership (Rankin, 1993).

- Ecological/Educational Rehabilitation Practices

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

- Advocacy Statements 1994. Burns P, Shields R, Minnich CA, Breese P, Rocchio C, Detelich L, Tucker C, Roeble A, Priest C, Fedor D, Corneliussen C, Garvin L, Rhule J, Gall M, Cabrera M, Cannon P. Advocacy Statements of 6 Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA) Funded, TBI Centers. Consumers and Advocates drafted Nov. 9-11, 1994, published in Life After Brain Injury: Answers I Can Live With, OSERS Conference. P.V.

- Alabama TBI Work Team. 1993. ICBM Interactive community based model: A guide for vocational rehabilitation professionals serving clients with head injury. Department of Education, Division of Rehabilitation Services.

- Bauser N. From the patient's point of view. J Cog Rehab Jan 1993; p 2-5.

- Blackerby WF. Rediscovering Intimacy after Head Injury. TBI Challenge, Fall 1993; 4:4-9.

- Bogdan A. The Survivor Perspective. In: Condeluci A, Ferris L, Outcome and Value. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 1992;7:37-45.

- Bogner J. Improving Outcomes Following Brain Injury. A longitudinal study at the Ohio Valley Center on TBI Prevention and Rehabilitation. Ohio State University. 1995.

- Bolden G. The Significance of family involvement through rehabilitation. Presentation: The Head Injury Community's Advances in Rehabilitation: Answering the Needs of Survivors and Families in the 90's. JMA Foundation, Baltimore MD. 1992.

- Brady JS. Partnerships for the 21st Century. Presentation to the ICON Employment /Community Services annual corporation/community event, Partnerships for the 21st Century. Fairfax VA. May 1994.

- Brain Injury Association, Inc., 105 N. Alfred St., Alexandria, VA 22314. Phone: 703/236-6000 and Helpline 1-800-444-6443. Website: http:// www.biausa.org.

- Brain Injury Association of Virginia. Coping With Traumatic Brain Injury: A Family Handbook. 1994. Richmond VA.

- Brain Injury Society. Menucha Fogel, Founder. 1901 Avenue N-Suite 5E, Brooklyn, NY 11230. Phone: 718/645-9733. E-mail: bis@virtualtrials.com, Website: http:// www.virtualtrials.com/bis.

- Bryant B. In Search Of Wings. South Paris ME: Wings Publishing.

- Bryant B. Who's outcome is it anyhow? Recognizing the right to fail, and the will to succeed. Presentation: BIA National Symposium, 1996.

- Campbell-Korves M. Participant Action Research. The consumer perspective presented in the 1995 PAR video. Source: TBI-NET Spring 1996, Vol. IV, 1:5. Mt. Sinai Medical Center Research & Training Center on Community Integration of Individuals with TBI.

- Cannon P. Survivor's Voice: Life is a journey of healing. TBI Challenge. Spring 1994; 2:2 pg.36.

- Cohen, A. and Rein, L. 1992. "The effect of head trauma on the visual system: The doctor of optometry as a member of the rehabilitation team." Journal of the American Optometric Association, v. 63, pp. 530-536.

- Cleveland L. TBI Outcomes Timelines: A closer look. Viewpoints, Issues in Brain Injury Rehabilitation. Fall 1997;36:2.

- Corrigan J. "Community Integration Following Traumatic Brain Injury." Table: Barriers to Optimal Quality of Life. NeuroRehabilitation, An Interdisciplinary Journal 1994; Vol.4 #2:109-121.

- Corthell D (ed). Traumatic brain injury and vocational rehabilitation. Menomonie, Wisconsin: Research and Training Center, Stout Vocational Rehabilitation Institute, School of Education and Human Services, University of Wisconsin-Stout, 1990.

- Dolen CE. Use of Community Services by Adult Head Injury Survivors in San Diego County, California. Masters Thesis. 1991.

- Dolen CE. Rewiring the brain: A lifeline to new connections after injury. Delray Beach Florida: St. Lucie Press, in press.

- Durgin CJ, Schmidt ND, Fryer LJ (eds). Staff development and clinical intervention in brain injury rehabilitation. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen, 1993.

- Fogel, MK. Why the Brain Injury Society? Serving Acquired and Traumatic Brain Injury Individuals and their Families. August 1998. Website: http:// www.virtualtrails.com/bis.

- GAO/HEHS-98-55. United States General Accounting Office: Report to Congressional Requesters. TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY, Programs Supporting Long-Term Services in Selected States. pp.1-4. The GAO Report available at 202/512-6000 or FAX: 202/512-6061 or TDD 202/512-2537. The GAO website is http:// www.gao.gov

- Gianutsos, R. and Suchoff, I. 1988. "Neuropsychological consequences of mild brain injury and optometric implications." Journal of Behavioral Optometry, 9:1, pp. 2-6.

- Gordon W, Issue Editor. Living in the community with brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, August 1998; Vol.13 #4.

- Gwin L. CONGRESSIONAL HEARING: Rehabilitation Facilities for People With Head Injuries. 1992. see Watson.

- Gwin L. (editor) Mouth, Voice of the Disability Nation. Rochester NY: Free Hand Press. Member of the Independent Press Association.

- Hibbard MR, Uysal S, Sliwinski M, Gordon W. Undiagnosed Health issues in individuals with traumatic brain injury living in the community. J Head Trauma Rehabilitation August 1998;Vol.13#4:47-57.

- Jacobs, H. and DeMello, C. 1995. "Consumer Directed Community Programming: The Traumatic Brain Injury Clubhouse" in the Brain Injury Association's 14th Annual Symposium on Defining Quality Outcomes, December 1995.

- Joseph, A. 1998. "What types of psychiatric problems can a person with brain injury experience?" Brain Injury Source, 2:1 p. 52.

- Kuoch T. Cultural Perspective. Presentation: Brain Injury Association Annual Symposium, Philadelphia PA, 1997.

- Lazzaretti T. A personal perspective on the value of rehabilitation. In: Durgin CJ, Schmidt ND, Fryer LJ. Staff development and clinical intervention in brain injury rehabilitation. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen, 1993.

- Life After Brain Injury: Answers I Can Live With. National Conference Syllabus, Office of Special Education & Rehab Services (OSERS), United States Department of Education, Nov. 1994.

- Lucas S. Acquired Brain Injury Diagram. Adapted from savage RC, Wolcott GF, 1994. Overview of acquired brain injury. In RC Savage and GF Wolcotte (Eds.), Educational Dimensions of acquired brain injury (pp. 3-12). Austin TX: Pro.ed.

- Ludlam, W. 1996. "Rehabilitation of traumatic brain injury with associated visual dysfunction -- A Case Report." NeuroRehabilitation, v.6. pp. 183-192

- Miller C, Campbell K. From The Ashes: A head injury self-advocacy guide. Seattle, Washington: The Phoenix Project, 1988. Website: www.headinjury.com

- Moeller K 1994. Compensatory Skills Training: Meeting the Challenges of the Workplace. TBI Challenge! Fall 1994;4: 12-13.

- Moeller K. The BRAIN BOOK@ Life Management System: a compensatory skill and residual strength building program for persons with brain injury. "Using Memory as a STRENGTH" Website on the BRAIN BOOK: http:// www.brainbook.com, 1998.

- Morgan A. Multicultural Health: Are there discrepancies? Presentation: by Morgan A, Barba C, Chief Standing Bear of the Mohegan Tribe and Kuoch MA: BIA Annual Symposium 1997 Brain Injury Assoc. Annual Symposium 1997.

- Murphy D. Survivor Perspectives: My Experience with Brain Injury. Brain Injury Press: San Diego Brain Injury Foundation. April 1996;150:6.

- Navigating a Future: Stories From Persons With Brain Injuries. Mount Sinai Medical Center. Grant #H128A000222 from the Rehabilitation Services Administration, U.S. Department of Education, 1994

- The Needs Conference for Underserved Consumers with Head Injury. See Youngbauer. Report 2 from the Research and Training Center on Independent Living for Underserved Populations, University of Kansas. Grant #H133B30012-94 from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, 1994.

- Nelson A, Smigieldski J. Problems needing solutions, A Consumer and Family Perspective. In: Corthell,eds. Traumatic brain injury and vocational rehabilitation. Menomonie, Wisconsin: Research and Training Center, University of Wisconsin-Stout, 1990.

- Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM) 1998. National Institutes of Health: Information Center, Rockville MD. (301) 402-2466.

- Osborn C.L. Over My Head: a doctor's own story of head injury from the inside looking out. Kansas City:Andrews McMeel Publishing. 1998.

- Palmer D. (managing editor) Brain Injury Connection, connecting survivors, caregivers, providers and the community. E-mail: BIConnect@aol.com. The BIC Website housed on the Brain Injury Help (Moeller) http:// www .tbihelp.com/BIC, 1998.

- Patrick P. Recovery Beyond Rehabilitation. Presentation: Journey Toward Independence, NVBIA Annual Conference 1996.

- Peterson AR. A Family's Growth and Change: A continuous evolution. Viewpoints, Fall 1995;31:3.

- Prioritized Services for Persons with Physical, Cognitive, & Sensory Impairment (Model of Components). Presented at: MidAtlantic Traumatic Brain Injury Consortium, Alexandria, VA. 1998. Source: James Brooker, member of the Disability Services Planning Workgroup Report on Service Priorities (Virginia Institute on Developmental Disabilities) to HJR 45. The Beyer Commission, State of Virginia: Final Report of the Commission on the Coordination of the Delivery of Services to Facilitate the Self Sufficiency and Support of Persons with Physical and Sensory Disabilities in the Commonwealth, 1991.

- Project LINCS. San Diego Community College District. OSERS GRANT H128A91068 1992. see Windsor 1993b.

- Racino JA, Williams JM. Living in the community: An examination of the philosophical and practical aspects. J Head Trauma 1994;9(2):35-48

- Rain K. Murdered and Still Here. Presentation: State of New York Department of Health Best Practices Conference 1996. Source: TBI Program Special Rept, New York State DOH January 1997.

- Rankin TM. Partnerships for the 21st Century: Report on the New Collaborations. ICON Employment Services. Alexandria VA 1993.

- Rhule-Stockton J. Empowerment: Self Discovery to Action. The Ohio Valley Center for Brain Injury Prevention and Rehabilitation. Columbus, Ohio, 1996.

- Rife J. Injured mind, shattered dreams. Brian's Journey from severe head injury to a new dream. Cambridge: Brookline Books 1994.

- Rocchio C. The Family Perspective on Psychotherapy Service. Brain Injury Source. Winter 1998;2:36-37.

- Rocchio C. Information and Preparation: The Key to Quality of Life After Brain Injury. Family News and Views. The Brain Injury Association. February 1996a.

- Rocchio C. A Family Guide to Alternative Therapies. Viewpoints, Issues in Brain Injury Rehabilitation 1996b;33:3.

- Rufing L. The Aztec Clubhouse. Head Injury Press April 1995; 138: 3. San Diego Brain Injury Foundation.

- Sander AM, Seel RT, Kreutzer JS, Hall KM, High WM, Rosenthal M. Agreement between persons with TBI and their relatives regarding psychosocial outcome using the community integration questionnaire. Arch Phys Med Rehab 1997; 78:353-57.

- State of Virginia, see "Prioritized Services for Persons with Physical, Cognitive, and Sensory Impairment".

- Spivack M, Balicki M. The Scope of the Problem. In: Corthell,eds. Traumatic brain injury and vocational rehab. U of Wisconsin 1990.

- Talbert B. Living with a Head Injury. The Journal of Cognitive Rehabilitation 1991; Special Issue, January:1-17.

- Taylor C. Was I absent the day they covered this in rehab? TBI Challenge Fall 1993; 4:16-18.

- Taylor DK. The Perspectives Network (TPN,Inc.) The TPN Magazine; On-Line Sites: WWW:http:// www.tbi.org, 1998

- TBI Consumer Report #1. Long Term Post TBI Health Problems. Publication of the RTC on Community Integration of Individuals with TBI. The Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York City. NIDRR. 1998

- TBI Consumer Report #2. Aerobic Exercise Following TBI. Publication of the RTC on Community Integration of Individuals with TBI. The Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York City. NIDRR. 1998

- Thomas DF, Menz FE, McAlees DC (eds). Community-based employment following traumatic brain injury. Menomonie, Wisconsin: Research and Training Center, Stout Vocational Rehabilitation Institute, School of Education and Human Services, University of Wisconsin-Stout, 1993.

- TPN, Inc. The Perspectives Network. Dena K. Taylor, Executive Director (dtaylor@tbi.org) P.O. Box 1859 Cumming GA 30028. Voice Mail: 800/685-6302 (USA only). The Perspectives Network URL: http:// www.tbi.org.

- TPN Magazine. 1996. This material is from TPN Magazine and is being reproduced and used with the express permission of TPN, Inc. Further usage/distribution/reproduction/retransmittal must be approved by TPN, Inc. Ph/FAX # (770) 844-6898.

- Vincent K. (editor) Brain Injury Guide, Networking Together. B.I.G., Lakeside CA. E-mail BIGKate4@aol.com. Website http:// members.aol.com/bigkate4/editor.htm., 1998.

- Watson S. Statement of Ms. Watson, President, Survivors Council NHIF. CONGRESSIONAL HEARING: Rehabilitation Facilities for People With Head Injuries. Human Resources and Intergovernmental Relations Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations, House of Representatives. ISBN 0-16-039167-9. February 19, 1992.pg 7-10.

- Williams, JM. Training staff for family-centered rehabilitation: Future directions in program planning. In: Durgin CJ, Schmidt ND, Fryer LJ. Staff development and clinical intervention in brain injury rehabilitation. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen, 1993.

- Windsor W. Advocating for Community Support Based Services Systems via Educational Models. Presentation: The Journey Toward Independence, Northern Virginia Brain Injury Association's Brain Injury Conference. Alexandria VA. 1993a.

- Windsor W. The Final Performance Report. Project LINCS: Learning in Natural Community Settings. DOE/OSERS/RSA: Innovative Strategies for Vocational Rehabilitation Services for Adults with Traumatic Brain Injury. San Diego Community College District. 1993b.

- Yaffe H, Fitzgerald R, Dunfee M, Wheatley D, Wurtzbacher M. 1994. Project CIRCLE: "Strategies for increasing choice, control, and competence for survivors of brain injuries in the vocational rehabilitation process." American Rehabilitation, 20:2,pp.20-31.

- Youngbauer J, Williams J, Mathews RM, Budde J. Report 2, The Needs Conference for Underserved Consumers with Head Injury. Research and Training Center on Independent Living for Underserved Populations, University of Kansas. Grant #H133B30012-94 from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, 1994.

Figure 1

Adapted by Stacy O. Lucas from: R.C. & Wolcott, G.F. (1994). Overview of acquired brain injury. In R.C. Savage & G.F. Wolcott (Eds.), Educational dimensions of acquired brain injury (pp. 3-12). Austin, TX: Pro-ed.

Used with permission from S. Lucas, adapted from Savage, R.C. and Wolcott, G.F. (1994)

Figure 2

ADVOCACY STATEMENTS OF 6 RSA FUNDED TBI CENTERS

OSERS Conference November 1994 - "Life After Brain Injury:

Finding Answers I Can Live With "

Rehabilitation ACT AMENDMENTS of 1992 "Congress finds that disability is a natural part of the human experience and in no way diminishes the right of individuals to live independently; enjoy self-determination; make choices; contribute to society; pursue meaningful careers; and enjoy full inclusion and integration in the economic political, social, cultural, and education mainstream of American society..." P.L. 102-569, Title 1, Section 101 (29 U.S.C. 701) Sec. 2

- Individuals and their families have the right to full disclosure (from health care professionals independent living centers, vocational rehabilitation, and other providers) of all community integration options available to them, including the option of returning home. Full disclosure includes such details as: cost, independence level, degree of individual and family control, program availability, social supports, length of stay, possible outcomes, location of options, and future planning.

- Persons with brain injury have the right to choose the routines of their lives. Personal routines may be as important to the persons as employment. When employment is not the choice, easily accessible community support and attention is helpful.

- Meaningful daily pursuits, as judged by the pursuer, are an integral part of the complexities and pleasures of life. Interference with such pursuits is a violation of civil rights as guaranteed by law. Choices regarding housing, employment, education, family, and social life must be protected.

- The cultural differences of individuals and their families must be recognized, respected and addressed by everyone. Language, customs, gender, religion, and socio-economic levels must not be allowed to impede access to needed resources. The values people hold and the choices they make must be supported and safeguarded.

- Individuals with brain in jury have the right to dream, to explore, to chose their own futures, to take risks, to try to succeed or fail like anyone else. They are individuals with many positive abilities and possibilities. A full exploration of options should never be sacrificed for the sake of ease, expediency or safety.

- Persons with brain injury have the right to choose where and with whom they live and to be a part of their neighborhood and community. They are free to choose whatever housing options they desire. Full inclusion into the community of their choice is the focus.

- Individuals with brain injury have the right to obtain the supports they need to overcome or compensate for their disability.

- Persons with brain injury have the right to determine their own needs. Informed consumers can make wise choices regarding what best meets their needs. With education, a consumer's choice is apt to be more effective and cost efficient than current systems that fund programs, not people.

- The responsibility of the service delivery system is to ensure all of the above and to support self-reliance, community connectedness, and facilitation of good self-advocacy skills among people with brain injury and their families. The ultimate desired outcome is for the individual consumer to get what (s)he needs.

From: "Life After Brain Injury" (1994)

Figure 3 Community Integration: Barriers to Optimal Quality of Life

| Question | Common Problems |

|---|---|

| How long will I live? |

|

| What will I live on? |

|

| Where will I live? |

|

| What will I do? |

|

| Whom will I love? |

|

| How much choice will I have about the first five questions? |

|

Corrigan J. "Community Integration Following Traumatic Brain Injury." Table: Barriers to Optimal Quality of Life. NeuroRehabilitation, An Interdisciplinary Journal 1994; Vol. 4 #2:109-121. Table 2, pg. 113, copyright 1994, reprinted with persmission from Elservier Science

Figure 4

Source: State of Virginia (1991)

Figure 5 Navigating a Future

Is a publication with stories from people with brain injuries written to illustrate the following Principles of Empowerment and Self Advocacy:

- People with brain injuries are entitled to live in the least restrictive environment.

- People with brain injuries need individualized supports to achieve independence.

- People with brain injuries, their families, and their employers need to be educated regarding the effects of brain injuries.

- People with brain injuries need active advocacy to negotiate bureaucratic systems.

- Resources for people with brain injuries should be managed and directed by the person and/or family.

- Service providers need to understand the cultural as well as the medical profiles of the persons they serve.

- People with brain injuries can inspire and educate communities.

- Medical, educational, and vocational professionals need specialized brain injury resources to assist them in meeting the needs of people with brain injuries.

- People with brain injuries and challenging behavior need individually designed programs to effectuate community re-entry.

- Family contact and preferences should be encouraged and respected in developing service plans.

- Technical assistance should be available in the community and in private homes, not restricted to rehabilitation facilities or vocational day programs.

- Programs for people with brain injuries must be flexible with regard to milestones and goals.

- Individuals and their families need to be given timely and full disclosure regarding choices available to them for rehabilitation services.

- People with brain injuries are people first.

Navigating a Future is a publication of the Comprehensive Regional Brain Injury Rehabilitation & Prevention Center, the Dept. of Rehabilitation Medicine, Mt. Sinai Medical Center. New York. Support for the Regional Center came from Grant #H128A000222, the Rehabilitation Services Administration, U.S. Department of Education, Washington, D.C. (1994)

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP