There appears to be no benefit to treating mildly low thyroid function during pregnancy, according to a study by a National Institutes of Health research network.

Markedly low thyroid function during pregnancy has long been associated with impaired fetal neurological development and increased risk for preterm birth and miscarriage. Similarly, some studies have indicated that even mildly low thyroid function (subclinical hypothyroidism) could possibly affect a newborn’s cognitive development and increase the chances for pregnancy and birth complications.

Now, a large, long-term study has found no differences in cognitive functioning among children born to mothers with subclinical hypothyroidism who were treated with medication during pregnancy and children whose mothers were not treated for the condition. The study also found no differences between the groups in rates of preterm birth, stillbirth, miscarriage and gestational diabetes.

The study, appearing in the New England Journal of Medicine, was conducted by the Maternal Fetal Medicine Units Network, a clinical research consortium funded by NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke also funded the study.

“Our results do not support routine thyroid screening in pregnancy since treatment did not improve maternal or infant outcomes,” said study author Uma Reddy, M.D., of the NICHD Pregnancy and Perinatology Branch.

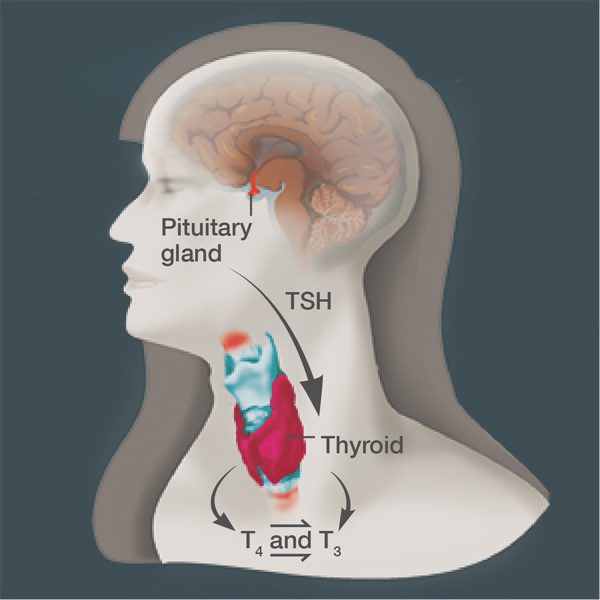

From October 2006 to October 2009, researchers at 15 centers in the network tested thyroid hormone levels of more than 97,000 women before the 20th week of pregnancy. Women in the study were screened for elevated levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)—an indicator of reduced thyroid function—but normal levels of the thyroid hormone thyroxine (T4). They also were screened for lower levels of T4—another potential marker of reduced thyroid function—but normal levels of TSH.

Researchers randomly assigned 677 women with mildly elevated levels of TSH to receive treatment with the drug levothyroxine (a synthetic form of T4) or a placebo. Additionally, 526 women with mildly low T4 levels were randomized to receive the drug or a placebo. Children born to women in all the groups underwent IQ testing and were assessed by child development specialists each year until they were 5 years of age.

Researchers found no significant differences between the treated and untreated groups in pregnancy complications, such as gestational diabetes or preeclampsia (high blood pressure during pregnancy). Among newborns, there were no differences in rates of stillbirth, death, birthweight, or respiratory problems. Similarly, there were no differences in the results of developmental assessments between the two groups of children through age five.

The study results confirm those of an earlier trial  which screened about 22,000 women and followed their infants until age 3.

which screened about 22,000 women and followed their infants until age 3.

###

About the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD): NICHD conducts and supports research in the United States and throughout the world on fetal, infant and child development; maternal, child and family health; reproductive biology and population issues; and medical rehabilitation. For more information, visit NICHD’s website.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit http://www.nih.gov.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP