A bacterial species that causes chorioamnionitis—an infection of the placenta and fetal membranes that often leads to preterm birth—relies on a gene for metal tolerance to hijack immune cells, suggests a study in mice funded by the National Institutes of Health. The findings indicate that strategies to target the gene and its products could eliminate one of the most common causes of preterm birth.

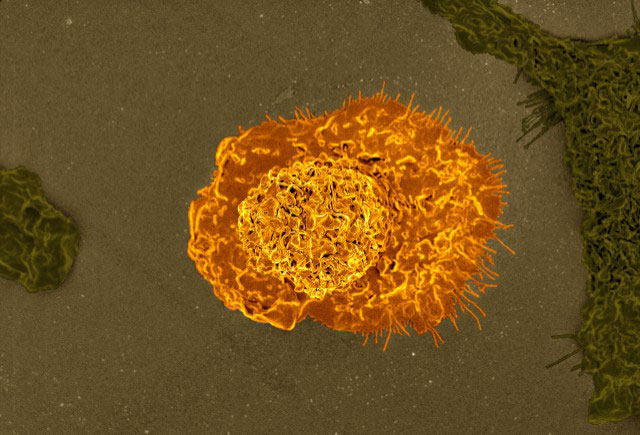

Maternal infection with Streptococcus agalactiae, or Group B Strep, is associated with preterm birth, blood infection in newborns, and stillbirth. The researchers found that strains of the bacteria that have a gene for tolerating the toxic effects of zinc and other metals colonize immune cells, using them to travel through the birth canal to infect the placenta and membranes surrounding the fetus. The bacteria are engulfed by immune cells called macrophages, which seal them in membrane-bound sacks taken inside the cells. The macrophages produce zinc inside the sacks, designed to poison the captive microbes. However, the gene cadD, allows the bacteria to thrive inside the macrophage, which they ride in to travel to the placenta and adjacent tissues.

The study was conducted by Jennifer A. Gaddy, Ph.D., of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and colleagues. It appears in Nature Communications. The study was funded by NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Background

Several species of bacteria have been identified as causes of chorioamnionitis, and Group B Strep accounts for 8-11% of all cases. The bacteria inhabit the intestinal tract, where it typically does not cause disease, and it may also colonize the vagina. Group B Strep colonizes an estimated 15-30% of pregnant women. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that pregnant women be screened for Group B Strep in the 36th through 38th week of pregnancy, and those who test positive should be treated with antibiotics.

Previous studies have shown that macrophages kill bacteria by engulfing them in membrane-bound sacks called phagolysosomes. The macrophages concentrate metals such as zinc in the phagolysosomes, which poison the bacteria. In an earlier study, the authors found that bacteria that survived in cultures with macrophages had a gene, cadD, that allowed them to tolerate high concentrations of metals.

They conducted the current study to determine how Group B Strep, a bacterium incapable of continuous movement on its own, could travel from the vagina into the uterus to infect the placenta and fetal membranes.

Results

Researchers found that Group B Strep with a deactivated cadD gene failed to colonize the placenta in pregnant mice. However, when they inserted an active cadD gene into the bacteria, the ability to infect the placenta and nearby fetal tissues was restored. In mice in which macrophages had been removed from the animals’ reproductive tracts, bacteria with active cadD genes failed to travel beyond the site of initial infection, indicating that functioning macrophages were needed to transport them into the placenta.

Significance

“Group B Streptococcus highjacks macrophages as a Trojan horse to invade the reproductive tract, cross the placenta, and infect the fetus,” Dr. Gaddy said.

The authors concluded that the findings could inform new strategies for preventing Group B strep during pregnancy.

Reference

Korir, ML et al. Streptococcus agalactiae cadD alleviates metal stress and promotes intracellular survival in macrophages and ascending infection during pregnancy. Nature Communications. 2022.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP