Credit: NICHD/NIH

NICHD researcher Mary Dasso, Ph.D., considers herself to have been lucky at many points in her career. But luck alone cannot account for her success as a principal investigator and program leader. Over the decades, Dr. Dasso has balanced hard work, drive, and ability to answer tough scientific questions, with a strong dose of reality.

“As a researcher, you need to balance passion and practicality. You need to care about what you’re studying. If you really love it, you’ll be good at it. Do what you love, but be sure to publish papers,” she said.

Growing up in Oregon

Studying in Cambridge

Switching Research Tracks

Building a Career at NIH

Raising a Family of New Scientists

Looking (Far) Ahead

Growing up in Oregon

Dr. Dasso was raised in Eugene, Oregon, along with her three siblings. Her father was a professor at the Lundquist College of Business at the University of Oregon, and her mother was a homemaker. She remembers spending a lot of time outdoors and on camping trips with her family.

“Growing up in Oregon was great. There was so much wilderness, which had a huge influence on me as a child. It’s a place with forests, coastlines, and deserts that have an amazing variety of flora and fauna, and you’re constantly surrounded by it,” she recalled fondly.

Credit: Jerome Dasso

The love of the outdoors made biology a particularly interesting topic for Dr. Dasso when she started school. She remembers learning about Mendelian genetics in junior high school and thinking that “it was the coolest thing ever.” At age 15, she took university summer classes on human genetics and evolutionary biology, which started her interest in larger scientific questions, such as how biology shapes human lives and the environment.

When it was time for college, at her parents urging, she attended the University of Oregon, where she assumed she would eventually go to law school, as her brother did. But because there was no pre-law degree, she chose to major in biochemistry, a topic that she felt would be “entertaining” for undergraduate work.

She had her first major stroke of luck after her sophomore year when she applied for a summer position in the laboratory of Pete von Hippel, Ph.D . She recalls the fellowship as “an amazing experience.”

“Pete was a marvelous mentor and a wonderful person. He had an ‘Everything’s good, let’s go!’ attitude and provided enthusiastic support.”

In his lab, she studied the function of T4 DNA polymerase, which is now commonly used by researchers to mutate genes of interest and conduct DNA-related studies. She continued in his lab through the rest of her time in Oregon, and those studies became the basis of her Honors College thesis. In 1984, Dr. Dasso graduated summa cum laude with a major in chemistry and a minor in mathematics.

Studying in Cambridge

Credit: Mary Dasso, Ph.D.

Her second lucky break came when a friend told her about the Marshall Scholarship program, which brought “intellectually distinguished young Americans” to study in the United Kingdom. After applying on a whim, she was selected and moved to Cambridge to begin her Marshall studies.

Dr. Dasso views the Marshall Scholarship as instrumental in setting her on the research path. Unlike programs in the United States, U.K. graduate students did not rotate in different labs. Students picked one lab and stayed there from start to finish. Dr. Dasso chose to work with Richard Jackson, Ph.D. , and Tim Hunt, Ph.D. (who would later win a Nobel Prize), at the University of Cambridge and, again, found herself with great mentors.

“I was completely naïve and thought that their research looked interesting, although I had never met either of them in person. It turned out to be super, blind luck.”

Dr. Dasso studied the initiation of eukaryotic mRNA translation, examining how the cells of complex organisms, such as plants and animals, turned DNA instructions into new proteins. Her scholarship was initially set for 2 years, but she successfully applied for an additional third year so that she could earn her doctoral degree.

“Beyond working with Richard and Tim, I now look back and appreciate Cambridge as a place with tons of brilliant people from all over the world. Working there was a privilege,” she noted. “And I’m still frequently impressed when I run into one of my former peers because they have gone on to do impressive things.”

Switching Research Tracks

Like many graduate students, Dr. Dasso considered other career options toward the end of her Ph.D. studies. She even asked her sister to send her a Peace Corps application, but it never arrived in the mail (Instead, her sister completed the application for herself and went to Africa). With an empty mailbox, Dr. Dasso gave science another try and applied for a Damon Runyon Walter Winchell Cancer Fund Fellowship to study with John W. Newport, Ph.D. , at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). She started her work at UCSD at the end of 1988.

With her interest in cell cycle research, which explores precisely how a cell replicates and divides into two cells, Dr. Dasso’s move to Dr. Newport’s lab made sense; he was a well-known cell biologist who worked on DNA replication and cell cycle control. In his lab, Dr. Dasso published her first major postdoctoral paper in 1990; it came together quickly because new systems to study cell cycle in vitro, using frog egg extracts, had recently been developed. Her project identified checkpoints that ensured DNA replication finished before the next step of cell division, called mitosis, began.

Credit: Mary Dasso, Ph.D.

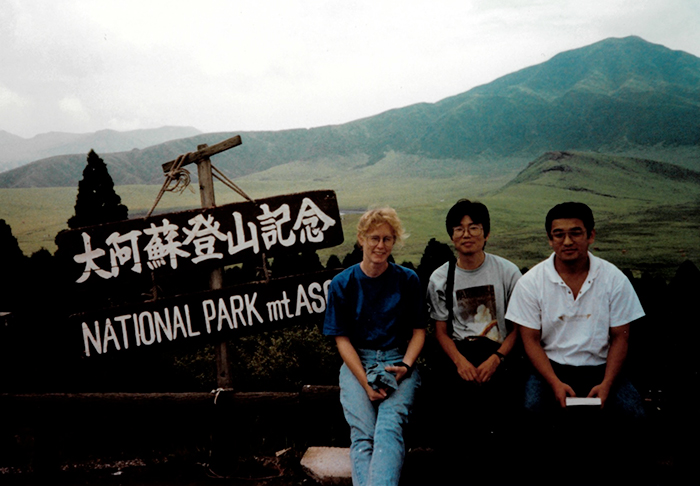

Dr. Dasso then expanded her work, looking for proteins involved in the replication checkpoint, which led her to a collaboration with the lab of Takeharu Nishimoto, Ph.D., at Kyushu University in Japan. Years earlier, Dr. Nishimoto had shown that cells without the RCC1 protein attempted to divide before completing DNA replication, resulting in catastrophic damage to chromosomes; he also identified the gene, RCC1, that made the protein. Dr. Nishimoto first sent a postdoctoral researcher, Hideo Nishitani, Ph.D., to conduct RCC1 experiments in Dr. Newport’s lab at UCSD. Then, Dr. Dasso went to Japan to complete more experiments.

The time in Japan was a “wonderful and eye-opening experience” for Dr. Dasso, both in learning about mammalian genetics in Dr. Nishimoto’s lab and in talking with her hardworking (all male) peers. These discussions prompted Dr. Dasso to think more about how cultural factors could advance or hinder the careers of male and female scientists. Members of the Nishimoto lab also provided invaluable advice for Dasso’s several weeks of travel after the experiments, one of the most memorable and enjoyable vacations of her life to date. Most importantly, this trip was a turning point in establishing the direction of her future research.

“Everything we’ve done since then came from those studies,” remarked Dr. Dasso, who brought her cell cycle projects to NIH.

Building a Career at NIH

After 4 years in San Diego, Dr. Dasso felt ready to move. She applied for a staff scientist position with Alan Wolffe, Ph.D. , who led the Laboratory of Molecular Embryology at NICHD. Dr. Dasso wanted to study how RCC1 interacted with chromatin (the DNA of chromosomes plus DNA-associated proteins), and Dr. Wolffe was working on all aspects of chromatin. In just 2 years, her diligent research led her to an independent, tenure-track position in 1994. She received tenure in 2000 and now leads her lab in the Section on Cell Cycle Regulation.

Credit: Dasso publication, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11854305

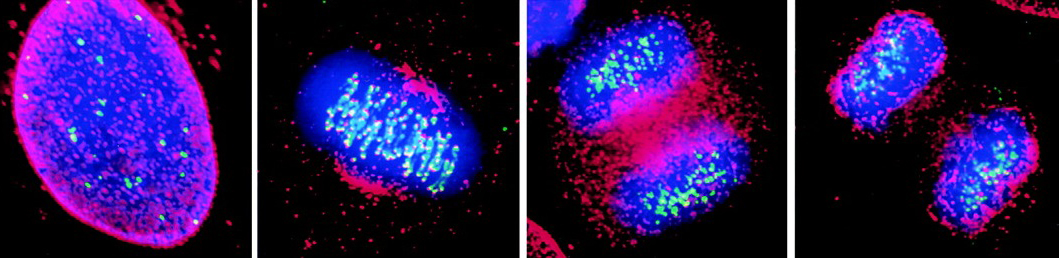

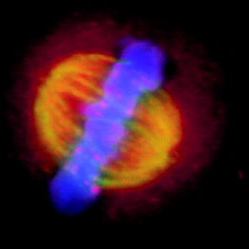

Dr. Dasso has published more than 100 research papers, but several stand out in their scientific impact and in the lessons she learned as an investigator. One study on Ran, a protein that helps move other proteins between the nucleus and the rest of the cell, published in 1999, was viewed as such a challenge to existing dogma that many people told her to stop working on it. At the time, many people believed that phenotypes or problems with Ran stemmed only from its role in nuclear transport. Dr. Dasso’s work showed that Ran actually had distinct, dual roles: one in nuclear transport and another in organizing the chromosome segregation apparatus, called the spindle, during mitosis.

Credit: Dasso publication, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11854305

“These results helped us understand how chromosomes organize other parts of the cell around themselves throughout the cell cycle. In mitosis, particularly, we showed that the chromosomes use Ran to orient the spindle. It was a complete change of thinking about how chromosomes communicate with the rest of the cell,” she said.

“There’s a famous old quote from Dan Mazia that ‘chromosomes in mitosis are like a corpse at a funeral. They’re the reason for the event but not an active participant.’ Understanding how Ran contributes to spindle assembly changed everything because the chromosomes were in fact the life of the party,” she added. After some initial skepticism, the paper was accepted, and within 6 months of publication, four papers from other labs verified the results.

Dr. Dasso also published key findings on the small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) pathway that then contributed to the discovery of SUMOylation, a process in which proteins are tagged by SUMO proteins, thereby modifying the tagged protein’s function. SUMOylation is integral to many cellular processes, including nuclear transport, cell cycle progression, protein stability, and stress responses. In 2010, her team showed that the SUMO protein SENP6 was essential for assembling the kinetochore, another key structure that forms during mitosis.

Her lab also identified the direct, physical relationship between nucleoporins—proteins found at pores around the nucleus—and the mitotic spindle (work published in 2002 and 2010). Today, her lab continues to study the nuclear pore, applying new technologies like CRISPR to understand the roles of the pore’s individual components. Her team is also working on IRBIT, another key protein in the cell cycle that they identified in 2014. Their work showed that IRBIT controls the abundance of deoxyribonucleotides, the building blocks for DNA synthesis.

For her efforts, Dr. Dasso has received numerous accolades, including NIH Merit, Innovation, and Mentor awards. She was elected to the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2018, the American Society for Cell Biology in 2019, and serves on several journal editorial boards, including Developmental Cell.

“I love science. Science is a wonderful career. You basically get paid to play all day, how great is that?” she said. “NICHD is a great environment, particularly starting out. I’ve always enjoyed my colleagues. I wouldn’t trade having been here for going anywhere else.”

Raising a Family of New Scientists

Dr. Dasso’s family includes her husband and their two daughters, who are now starting their own careers in science, technology, engineering, mathematics (STEM) fields. She hopes that changes in the workplace will make balancing family and career more straightforward for them and for upcoming female scientists.

“There’s more discussion now about work-life balance and the importance of keeping careers intact through life challenges, such as taking care of children or aging parents. This is very positive for both individuals and institutions, and I hope that the scientific community continues to innovate and improve in this direction.”

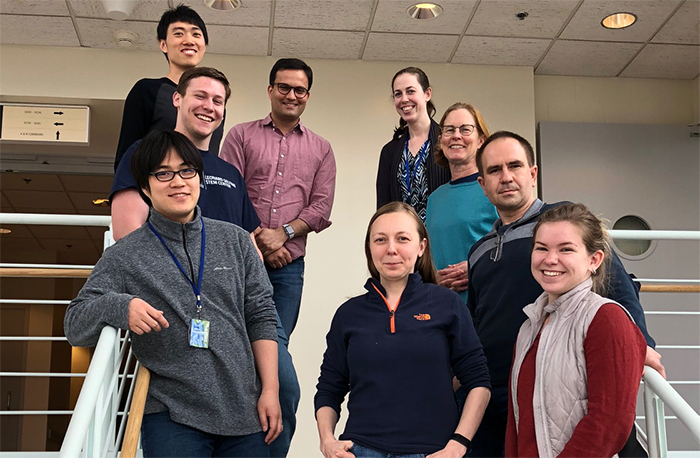

Current and former trainees also note being deeply indebted to Dr. Dasso for her leadership and guidance.

“Dr. Dasso is the kind of mentor a young scientist wants to have—someone who has risen to the top of her field and is generous with her support and time with young colleagues. She is a world-class scientist who continually challenges herself and her mentees. She has pushed me to forge collaborations, helping me understand that science is not a solitary affair, but rather a mixture of creative and scientific inputs. I am a better scientist because of her training,” said Saroj Regmi, Ph.D., a current postdoctoral fellow in Dasso’s lab.

Yoshiaki Azuma, Ph.D., a former postdoctoral fellow who now leads his own lab at the University of Kansas, said “Dr. Dasso’s open-minded attitude toward experimental results made me more aware of how important it is to evaluate results fairly, how to design better experiments, and how to connect daily experiments to larger biological questions. I also learned how important it is to motivate and encourage my lab members by having continuous, productive discussions between each member and myself, and stimulating discussion between lab members.”

“Dr. Dasso has been instrumental in my professional development as a female scientist,” explained Sarine Markossian, Ph.D., another former trainee who is now a senior scientist at the University of California, San Francisco. “Her mentorship went far beyond science into career development and professional advice. What strikes me the most about Mary is her growth mindset. I am always in awe of the amount of personal and professional growth I achieved while working with her.”

Looking (Far) Ahead

Credit: NICHD/NIH

In addition to running her lab, Dr. Dasso is also the Associate Scientific Director for Administration and Budget within NICHD’s intramural research program.

“I’m trying to think beyond the end of my own career. This should be true of any senior investigator. Once you’re at this point, how do you make the institution last and thrive over time? That not only means improving resources for everybody coming up—trainees and tenure-track investigators—but also bringing in new and diverse points of view to enrich our science,” she said.

During her time at NICHD, she has seen fluctuations in the percentage of labs led by female investigators. But now, she sees leaders building equity into the process. “It’s important to have diversity throughout the faculty at multiple levels. When people need to navigate a particular problem, they often find it easier to ask for advice from someone who shares a similar background and who might have had comparable experiences.”

Dr. Dasso is also acutely conscious of how a respectful, diverse community can positively impact both science and the lives of its members through their daily environment.

“Little things that people say can add to someone’s burden, just by being rude or disrespectful. I understand now that you don’t want to carelessly add to someone else’s burden that way. Incorporating and celebrating different perspectives not only creates a more welcoming environment, it also gives a much broader value to our science by allowing us to approach questions from multiple viewpoints,” she added.

“In the end, we’re all lucky to be here for the science regardless of where we started.”

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP