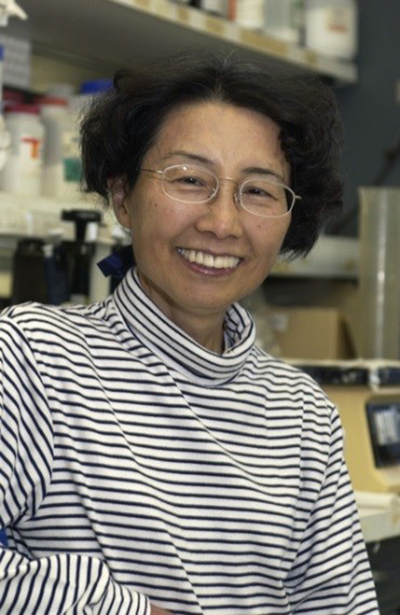

NICHD researcher Keiko Ozato, Ph.D., will turn 78 years old later this year. She gets to work by 7 a.m. on most mornings, leading a laboratory that she started back in 1981. Dr. Ozato considers NICHD to be one of the friendliest places for conducting basic research and exploring the fundamental mechanisms that underlie development. Her joy and appreciation stem from early experiences that were not so pleasant.

“On the day I started my graduate work, all of us [women] were called into the professor’s large office and told, ‘Hey girls, this is not a woman’s place. We will be very happy to help you get a job in a women’s college as a teacher. Think about it.’ That’s what we were told,” said Dr. Ozato about her time in Kyoto University during the 1960s and 1970s.

Early Years in Japan

Dr. Ozato was born in northern Japan in 1941, the same year that Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and the United States entered World War II. The war ended four years later, but as Dr. Ozato put it, “Everything was turned upside down. The Emperor was no longer almighty. What was valued culturally was trashed and replaced by a new American culture.” Like most Japanese families during that time, Dr. Ozato’s family was poor. Consecutive famines left Japan with very few resources. “Most kids were small and skinny and always hungry.”

Compounding the family’s poverty was her father’s battle with tuberculosis—a disease that affected many families in Japan. He did not have access to antibiotics until much later in life, so he suffered for quite a long time. The disease not only affected Dr. Ozato’s family and upbringing, but it would later influence her focus on immunology, the study of the body’s immune system.

Despite the challenges of growing up after World War II, certain values remained unchanged in Japan. People still respected science and encouraged children to pursue higher education. Dr. Ozato loved science; it appeared limitless in her young mind. Japan’s new Constitution gave women the right to vote and to receive the same education as men for the very first time, providing new sources of confidence.

In 1973, Dr. Ozato completed her graduate studies on cell differentiation—how cells reach their mature forms—with Tokindo S. Okada, Ph.D. , a well-known developmental biologist at Kyoto University. During that time, developmental biology was very different. DNA and RNA studies were not common, despite being a cornerstone to modern developmental biology today. The field was derived from classical embryology, which used frogs as a model organism. As the field evolved, pioneers like Drs. Okada and Ozato incorporated new models and new techniques.

Challenges for Women

While research itself is quite demanding, being a woman meant extra challenges for Dr. Ozato. She recalled that women made up roughly 10 percent of science students during her graduate school years in Japan. Professors didn’t quite know how to treat them, including the one who bluntly told them that they didn’t belong.

Dr. Ozato believes that the professors, though misguided, had meant well, at least in their own minds. “In Japanese society at the time, the guy in the family gets the salary, bread, rice, and everything. And the woman worked under him. And when you got older, you followed your sons,” she remarked.

Not surprisingly, none of her female colleagues heeded the advice of that professor. They all completed their studies, but they faced a new challenge upon graduation—getting a job. Dr. Ozato always assumed she would get a job. “I believed in the Constitution—as long as you got a good education, you’ll have a job. That was an unrealistic expectation.”

She looked for a job for an entire year, but no one offered her a position. Meanwhile, most of the men in her class got jobs. Some of the women did, too, but the posts were usually at colleges where teaching was the priority, not research.

Among those who didn’t get a job, some classmates confided that they decided to accept marriage proposals instead. “There was too much pressure, and some people didn’t want to fight against their parents. [They’re thinking], ‘So if I marry this guy, everyone in the family will be happy, so I’ll do that.’ Some women had to do that, no question about it,” said Dr. Ozato.

Luckily, Dr. Okada suggested that she pursue research in the United States. He wrote a letter of recommendation to one of his colleagues, James Ebert, Ph.D. , a prominent developmental biologist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington in Baltimore, Maryland. Dr. Ebert offered her a Carnegie Fellowship, and Dr. Ozato moved overseas for the first time. She recalled with a laugh, “At that time, I felt that I was expelled from Japan. So, I will never ever, never ever, go back to Japan.”

A Flourishing Career

Dr. Ozato worked as a postdoctoral researcher with Dr. Ebert until 1978, exploring immunology as a model for developmental biology. “The fact that antibody-producing cells may undergo mutation in the somatic state was a revolutionary finding. People argued about it, how this happened, whether this was common, as a principle of development. So, it was a very exciting time,” she said, in reference to how immune cells mutate on purpose to generate a range of antibodies.

During her postdoctoral years, she also met and married her husband, Igor Dawid, Ph.D., a fellow researcher. Dr. Ozato felt that part of their strong connection resulted from their shared immigrant and World War II experiences. Dr. Dawid’s father was from the Austro-Hungarian Empire and, because they were Jewish, his family constantly moved around Europe during the war. Some of his relatives died in Auschwitz. But he eventually earned his Ph.D. at the University of Vienna and came to the United States to pursue his own research career.

They both ended up at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1978. Dr. Ozato first worked as a staff fellow in the Experimental Immunology Branch at the National Cancer Institute, in the laboratory of David H. Sachs, M.D. Dr. Sachs ran the Transplantation Biology Section, where Dr. Ozato worked on the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), which plays a big role in tissue rejection for organ and bone marrow transplants. Her research helped explain the genetic basis for MHC differences and paved the way for modern tissue typing and transplant matching.

In 1981, NICHD recruited Dr. Ozato to start her own independent research lab. As she remembers it, NICHD was undergoing leadership changes with a new institute director, Mortimer B. Lipsett, M.D., and scientific director, James Sidbury, Jr., M.D. The institute had also recently lost prominent immunologist Philip Leder, M.D., to Harvard University, so it recruited Dr. Ozato, as well as John Robbins, M.D., and Rachel Schneerson, M.D., who both later developed a landmark vaccine for Hemophilus influenzae type b.

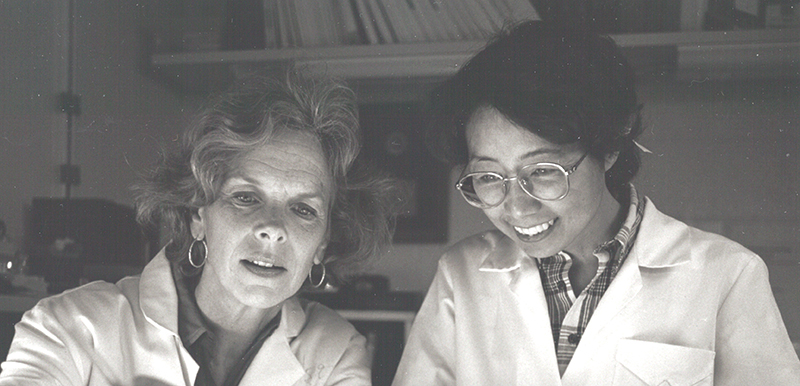

Describing her early years at NIH, working as a staff fellow, Dr. Ozato said, “I felt so liberated seeing other female postdocs. It was one of my ideal places to work, and I was so excited to be here. I felt, ‘Finally, I’m one of them.’” She received tenure in 1987 under scientific director Arthur Levine, M.D. To this day, her lab is the Section on Molecular Genetics of Immunity.

“The field advances as a community”

When asked about her scientific achievements, Dr. Ozato is remarkably humble, especially for a prolific researcher who has published more than 400 papers, including studies in top journals like Nature and Cell. “There are great scientists. But after all, it’s a community effort, a community achievement. I cannot say a single person has done everything. Most of the time, the field advances as a community.”

But Dr. Ozato’s colleagues are eager to talk about her achievements and impact, for the field and for subsequent generations of scientists. Her lab continues to explore the molecular mechanisms underlying innate immunity, including transcriptional gene regulation, which basically asks: how does an immune cell know what to do under different circumstances?

Dr. Ozato feels lucky to have gotten into the field early on, when most transcription factors were unknown (Transcription factors help a cell turn DNA instructions into action. They act like a cell’s foreman. Scientists estimate that people have more than 3,000 transcription factors ). Over the course of her career, Dr. Ozato refined techniques to discover transcription factors, which other scientists have used in their own work, and she identified several new transcription factors and regulators.

Two of the most important regulators discovered by her lab are IRF8 and BRD4.

IRF8 directs stem cells to develop into various innate immune cells, which have many roles and protect the body against bacteria, viruses, and other disease-causing microbes. It’s not lost on Dr. Ozato that IRF8 is essential for fighting off the bacteria that causes tuberculosis, the disease that affected her father. Because of the diverse role of immune cells, IRF8 is also considered a tumor suppressor gene, inhibiting the growth of blood cancers. It contributes to chronic inflammatory diseases, including heart disease, and autoimmune diseases, like multiple sclerosis.

BRD4 is important in epigenetics and reads signal marks on histones, proteins that help package and organize DNA into structures called chromatin. Dr. Ozato’s work, along with others, paved the way for the development of small molecule inhibitors that target BRD4 and proteins similar to it. These drugs are now promising therapeutic candidates for treating blood cancers and a range of inflammatory diseases.

Being nearly 78 hasn’t diminished Dr. Ozato’s passionate curiosity. Currently, she is studying the role of BRD4 in neuroinflammation and multiple sclerosis. She’s also refining the idea of cellular memory. “Immunological memory is one of the most important concepts in immunology, but it is limited to T and B lymphocytes. Neurons remember, and neurons keep memory. Most people think that the nervous and immune systems are the only two where memory works. But we now think that ordinary cells, including innate immune cells, also have the ability to make memory through chromatin. This memory improves the cell’s ability to respond to external cues. That’s what I’m really excited about.”

“I was able to continue”

Dr. Ozato shares that people often ask her when she will retire and what she will do. But she says that she cannot fathom retiring because most of her interests are in the lab. Despite challenges and feeling isolated at times in the past, either because she is a woman or because she is an immigrant, she has always prevailed. “Lab work is literally my way of life,” she said. “The bottom line: I was able to continue working. Even if there are difficulties, the research community allows anyone to pursue the American Dream.”

Her success is perhaps best illustrated by an award she received in 2012. She was given the Order of Sacred Treasure, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon—an honor bestowed by the Japanese government and the Emperor of Japan for her research achievements and contributions to the scientific community and to Japan. She, along with Stephen Katz, M.D., the former director of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, were honored in a ceremony at the residence of the Japanese ambassador, Ichiro Fujisaki, in Washington, D.C. The award also meant traveling to Tokyo to meet the Emperor of Japan, which she did, despite her earlier, impassioned vow to never return. Check out an article (PDF 1.75 MB) about the ceremony in the NIH Record .

Because of her experiences, Dr. Ozato is eager to mentor young scientists. While older researchers could argue that the young ones have it easier, she believes the opposite. Dr. Ozato thinks that young scientists face many new challenges, and that the older generation should help shoulder these burdens. She also has great admiration for young scientists, explaining that they’re often more informed, know what they want, and are better focused than scientists were when she was younger.

“I now realize how important it is to provide a nurturing environment for the younger generation. I’m not doing anything special, I’m just following NIH’s grand tradition.”

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP