Complications also more common in treated group, results of NIH study show

Surgery to repair pelvic organ prolapse often carries a risk of incontinence. To avoid scheduling a second surgery, some women may opt to have a second procedure to reduce incontinence at the time of their prolapse repair surgery.

A study funded by the National Institutes of Health has found that although the surgery— to support the urethra with a sling—reduces the rate of incontinence, it also carries the risk for such complications as difficulty emptying the bladder, urinary tract infection, bladder perforation, and bleeding.

The study authors concluded that, when deciding whether to have the second procedure at the same time as the first, women and their physicians consider the potential benefits together with the potential risks of having the two procedures at the same time.

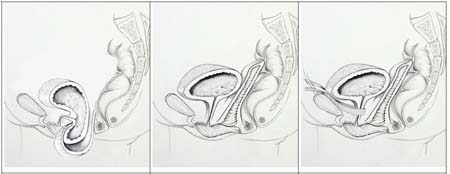

Pelvic Organ Prolapse occurs when muscles and tissues in the pelvic cavity weaken. The muscles and tissues span the lower pelvic cavity, holding such organs as the bladder, uterus and colon in place. With the weakening, the organs slump into the pelvic cavity, pressing into the vagina. In severe cases, the vagina is inverted, and vaginal tissue protrudes out of the body. As the pelvic organs shift, they can push the urethra out of place and alter the shape of the bladder. Prolapse repair surgery relieves the pressure on the lower pelvic cavity, but sometimes urinary incontinence develops. To reduce the risk of incontinence, the sling is threaded under the urethra and attached to the abdominal wall.

One in five women will have surgery to correct this condition in her lifetime, according to the study authors. Of the estimated 200,000 women who undergo surgery each year, about 25 percent become incontinent following surgery.

after surgical correction, and corrected pelvic organ prolapse with urethral sling.—Illustrations courtesy of Jasmine Tan-Kim, M.D.

“The idea has been that inserting a bladder sling—in conjunction with vaginal surgery to correct prolapse—would reduce incontinence and avoid the need for a second surgery,” said Susan F. Meikle, M.D., MSPH, of the Contraception and Reproductive Health Branch of the NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and Program Director of the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. “The study found that inserting the bladder sling may lead to complications. Although these complications can be treated, it may also make sense to wait for symptoms to appear before inserting the bladder sling.”

In addition to the NICHD, the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health also supported the study.

The study’s first author, John T. Wei, M.D., M.S., of the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor, conducted the study with Dr. Meikle and collaborators in the NICHD-supported Pelvic Floor Disorders Network.

Previously, Network studies reported on the frequency of pelvic disorders, including prolapse, among U.S. women and described how another kind of secondary procedure during abdominal prolapse surgery can reduce incontinence.

The findings appear in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The randomized study involved 337 who were treated surgically for prolapse. The women were in their early 60s, on average. Half of the women received a urethral sling at the time of their prolapse repair surgery to reduce the chance of incontinence after the pelvic organs are returned to a more normal position.

The researchers analyzed the rate of incontinence in the two groups. Within three months of surgery, researchers diagnosed incontinence in 24 percent of the women. The researchers found twice as many cases (49 percent) occurred among women with no sling. After 12 months had passed, 27 percent of the sling group had developed incontinence or been treated for it, compared with 43 percent in the no-sling group.

But the sling group was more likely to experience complications of surgery, the researchers found. These included urinary tract infections, major bleeding, bladder perforations, and difficulty emptying the bladder. In 2 percent of cases, women required additional surgery to take out the sling. In the group that did not receive a sling, about 5 percent of the women underwent additional surgery within a year to have a sling put in place.

Some doctors conduct a simple test to predict if a woman is likely to develop incontinence after prolapse repair surgery. Typically, a woman is asked to cough or mimic as sneeze when her bladder is full and the uterus is re-positioned to the top of the vaginal cavity. The logic of the test is that, if urine escapes, then incontinence is likely to result after the surgery.

###

About the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD)

The NICHD sponsors research on development, before and after birth; maternal, child, and family health; reproductive biology and population issues; and medical rehabilitation. For more information, visit the Institute’s website at http://www.nichd.nih.gov/.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH)

NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit http://www.nih.gov.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP