NIH-funded scientists find DNA repair systems, including BRCA1, become less efficient

Scientists supported by the National Institutes of Health have a new theory as to why a woman’s fertility declines after her mid-30s. They also suggest an approach that might help slow the process, enhancing and prolonging fertility.

They found that, as women age, their egg cells become riddled with DNA damage and die off because their DNA repair systems wear out. Defects in one of the DNA repair genes—BRCA1—have long been linked with breast cancer, and now also appear to cause early menopause.

“We all know that a woman’s fertility declines in her 40s. This study provides a molecular explanation for why that happens,” said Dr. Susan Taymans, Ph.D., of the Fertility and Infertility Branch of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the NIH institute that funded the study. “Eventually, such insights might help us find ways to improve and extend a woman’s reproductive life.”

The findings appear in Science Translational Medicine.

In general, a woman’s ability to conceive and maintain a pregnancy is linked to the number and health of her egg cells. Before a baby girl is born, her ovaries contain her lifetime supply of egg cells (known as primordial follicle oocytes) until they are more mature. As she enters her late 30s, the number of oocytes—and fertility—dips precipitously. By the time she reaches her early 50s, her original ovarian supply of about 1 million cells drops virtually to zero.

Only a small proportion of oocytes—about 500—are released via ovulation during the woman’s reproductive life. The remaining 99.9 percent are eliminated by the woman’s body, primarily through cellular suicide, a normal process that prevents the spread or inheritance of damaged cells.

The scientists suspect that most aging oocytes self-destruct because they have accumulated a dangerous type of DNA damage called double-stranded breaks. According to the study, older oocytes have more of this sort of damage than do younger ones. The researchers also found that older oocytes are less able to fix DNA breaks due to their dwindling supply of repair molecules.

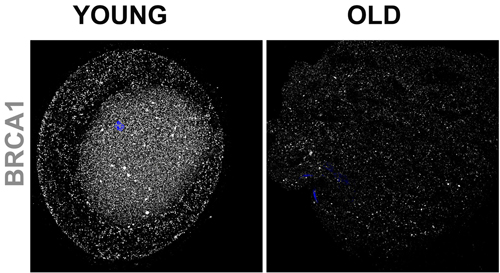

Examining oocytes from mice, and from women 24 to 41 years old, the researchers found that the activity of four DNA repair genes (BRCA1, MRE11, Rad51 and ATM) declined with age. When the research team experimentally turned off these genes in mouse oocytes, the cells had more DNA breaks and higher death rates than did oocytes with properly working repair systems.

The research team’s findings stemmed from their initial focus on BRCA1, a DNA repair gene that has been closely studied for nearly 20 years because defective versions of it dramatically increase a woman’s risk of breast cancer.

Using mice bred to lack the BRCA1 gene, the NICHD-supported scientists confirmed that a healthy version of BRCA1 is vital to reproductive health. BRCA1-deficient mice were less fertile, had fewer oocytes, and had more double-stranded DNA breaks in their remaining oocytes than did normal mice.

Abnormal BRCA1 appears to cause the same problems in humans—the team’s studies suggest that if a woman’s oocytes contain mutant versions of BRCA1, she will exhaust her ovarian supply sooner than women whose oocytes carry the healthy version of BRCA1.

Together, these findings show that the ability of oocytes to repair double-stranded DNA breaks is closely linked with ovarian aging and, by extension, a woman’s fertility. This molecular-level understanding points to new reproductive therapies. Specifically, the scientists suggest that finding ways to bolster DNA repair systems in the ovaries might lead to treatments that can improve or prolong fertility.

Senior author Kutluk Oktay, M.D., of New York Medical College (NYMC), in Rye and Valhalla, collaborated with colleagues at NYMC and researchers at Istanbul Bilim University, Turkey; Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York; and Yeshiva University, New York.

The work was supported by grants HD53112 and HD61259.

Image from Impairment of BRCA1-Related DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Leads to Ovarian Aging in Mice and Humans, Shiny Titus et al. Sci Transl Med 5, 172ra21 (2013); DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004925.

Download the high-resolution version of the image (JPG - 486 KB)

###

About the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD): The NICHD sponsors research on development, before and after birth; maternal, child, and family health; reproductive biology and population issues; and medical rehabilitation. For more information, visit the Institute’s website at http://www.nichd.nih.gov/.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit http://www.nih.gov.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP