Mouse Study May Lead to New Therapies for Parkinson’s Disease

Endometrial stem cells injected into the brains of mice with a laboratory-induced form of Parkinson’s disease appeared to take over the functioning of brain cells eradicated by the disease.

The finding raises the possibility that women with Parkinson’s disease could serve as their own stem cell donors. Similarly, because endometrial stem cells are readily available and easy to collect, banks of endometrial stem cells could be stored for men and women with Parkinson’s disease.

"These early results are encouraging," said Alan E. Guttmacher, M.D., acting director of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the NIH Institute that funded the study. "Endometrial stem cells are widely available, easy to access and appear to take on the characteristics of nervous system tissue readily."

Parkinson’s disease results from a loss of brain cells that produce the chemical messenger dopamine, which aids the transmission of brain signals that coordinate movement.

This is the first time that researchers have successfully transplanted stem cells derived from the endometrium, or the lining of the uterus, into another kind of tissue (the brain) and shown that these cells can develop into cells with the properties of that tissue.

The findings appear online in the Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine.

The study’s authors were Erin F. Wolff, Xiao-Bing Gao, Katherine V. Yao, Zane B. Andrews, Hongling Du, John D. Elsworth and Hugh S. Taylor, all of Yale University School of Medicine.

Stem cells retain the capacity to develop into a range of cell types with specific functions. They have been derived from umbilical cord blood, bone marrow, embryonic tissue, and from other tissues with an inherent capacity to develop into specialized cells. Because of their ability to divide into new cells and to develop into a variety of cell types, stem cells are considered promising for the treatment of many diseases in which the body’s own cells are damaged or depleted.

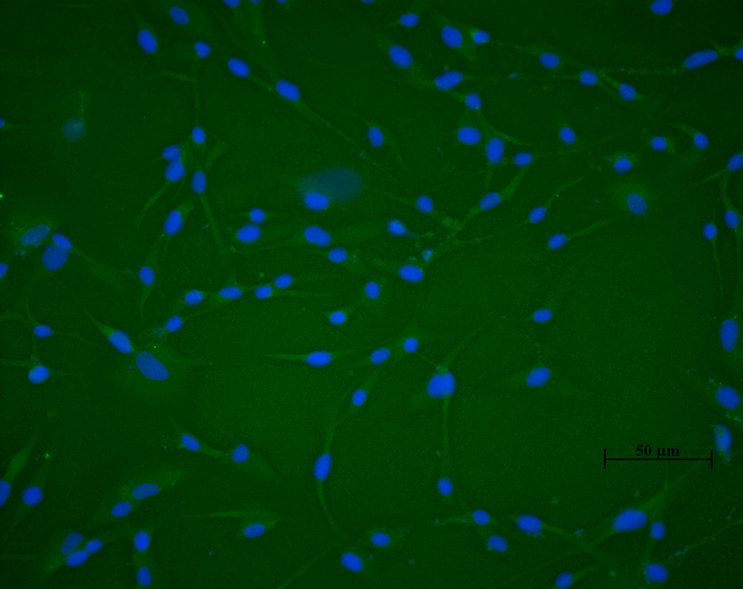

In the current study, the researchers generated stem cells using endometrial tissue obtained from nine women who did not have Parkinson’s disease and verified that, in laboratory cultures, the unspecialized endometrial stem cells could be transformed into dopamine-producing nerve cells like those in the brain.

The researchers also demonstrated that, when injected directly into the brains of mice with a Parkinson’s-like condition, endometrial stem cells would develop into dopamine-producing cells.

Unspecialized stem cells from the endometrial tissue were injected into mouse striatum, a structure deep in the brain that plays a vital role in coordinating balance and movement. When the researchers examined the animals’ striata five weeks later, they found that the stem cells had populated the striatum and an adjacent brain region, the substantia nigra. The substantia nigra produces abnormally low levels of dopamine in human Parkinson’s disease and the mouse version of the disorder. The researchers confirmed that the stem cells that had migrated to the substantia nigra became dopamine-producing nerve cells and that the animals’ dopamine levels were partially restored.

The study did not examine the longer-term effects of the stem cell transplants or evaluate any changes in the ability of the mice to move. The researchers noted that additional research would need to be conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the technique before it could be approved for human use.

According to the researchers, stem cells derived from endometrial tissue appear to be less likely to be rejected than are stem cells from other sources. As expected, the stem cells generated dopamine producing cells when transplanted into the brains of mice with compromised immune systems. However, the transplants also successfully gave rise to dopamine producing cells in the brains of mice with normal immune systems.

According to Dr. Taylor, because women could provide their own donor tissue, there would be no concern that their bodies would reject the implants. Moreover, because endometrial tissue is widely available, banks of stem cells could be established. The stem cells could be matched by tissue type to male recipients with Parkinson’s to minimize the chances of rejection.

In addition, Dr. Taylor added that endometrial stem cells might prove to be easier to obtain and easier to use than many other types of stem cells. With each menstrual cycle, women generate new endometrial tissue every month, so the stem cells are readily available. Even after menopause, women taking estrogen supplements are capable of generating new endometrial tissue. Because doctors can gather samples of the endometrial lining in a simple office procedure, it is also easier to collect than other types of adult stem cells, such as those from bone marrow, which must be collected surgically.

"Endometrial tissue is probably the most readily available, safest, most easily attainable source of stem cells that is currently available. We hope the cells we derived are the first of many types that will be used to treat a variety of diseases," said senior author Hugh S. Taylor, M.D., of Yale University. "I think this is just the tip of the iceberg for what we will be able to do with these cells."

###

The NICHD sponsors research on development, before and after birth; maternal, child, and family health; reproductive biology and population issues; and medical rehabilitation. For more information, visit the Institute’s Web site at http://www.nichd.nih.gov/.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) — The Nation's Medical Research Agency — includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. It is the primary federal agency for conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and it investigates the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit http://www.nih.gov.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP