Like many 10-year-olds, Ruby Cohen is passionate about Taylor Swift. The busy fifth grader also loves to draw, perform in musicals at her local community center, and runs her own small business selling colorful, cream-filled macarons.

Credit: Julie Cohen

But while some kids might save their sales profits for tickets to Swift’s Eras Tour, Ruby sends much of her macaron proceeds to Brylan’s Feat , a foundation that hosts Camp Watchme, a summer camp she enjoys for children like her who have lymphedema. Lymphedema arises from malformations of the lymphatic system and occurs when fluid drains abnormally into the spaces between tissue cells, resulting in chronic swelling (edema). A person with lymphedema often has edema in the arms and/or legs, but in some rarer forms, the condition affects organs such as the heart or lungs.

“Ruby is only affected in her left leg. She wears a compression garment from her mid foot to the groin and can customize them with different colors and patterns,” said Ruby’s father, Jared Cohen, M.D., a fellow in the division of oncology at Washington University School of Medicine. “At night we do multi-layer bandaging, but we’re blessed it's only one limb.”

Anomalies of the vascular system, which include lymphatic malformations, arise from hereditary or somatic—occurring spontaneously after conception—gene mutations. The exact prevalence of lymphatic malformations is unknown, though they are thought to affect 1 in 4,000 births. For Dr. Cohen and his wife, Julie, signs that something wasn’t right appeared when Ruby was 4 and had worrisome swelling in her toes and knee. That discovery sent the family on a long medical journey, which eventually brought them to NIH and Sarah Sheppard, M.D., Ph.D., a clinical investigator in NICHD’s Unit on Vascular Malformations.

The Sheppard Lab seeks to understand the genetic causes of vascular malformations and vascular anomalies more broadly, identify new and existing drugs to treat them, and support families caring for children with rare conditions. Ruby’s parents enrolled her in a study Dr. Sheppard is leading to understand the natural history and disease progression for those who have a subtype of lymphatic malformation known as a central conducting lymphatic anomaly (CCLA).

“Our goal is to understand how these disorders change over a lifetime. They are mosaic disorders, which means they don't affect every cell of the body, just some,” Dr. Sheppard said. “Because of this, each person affected may have different manifestations of the disease.”

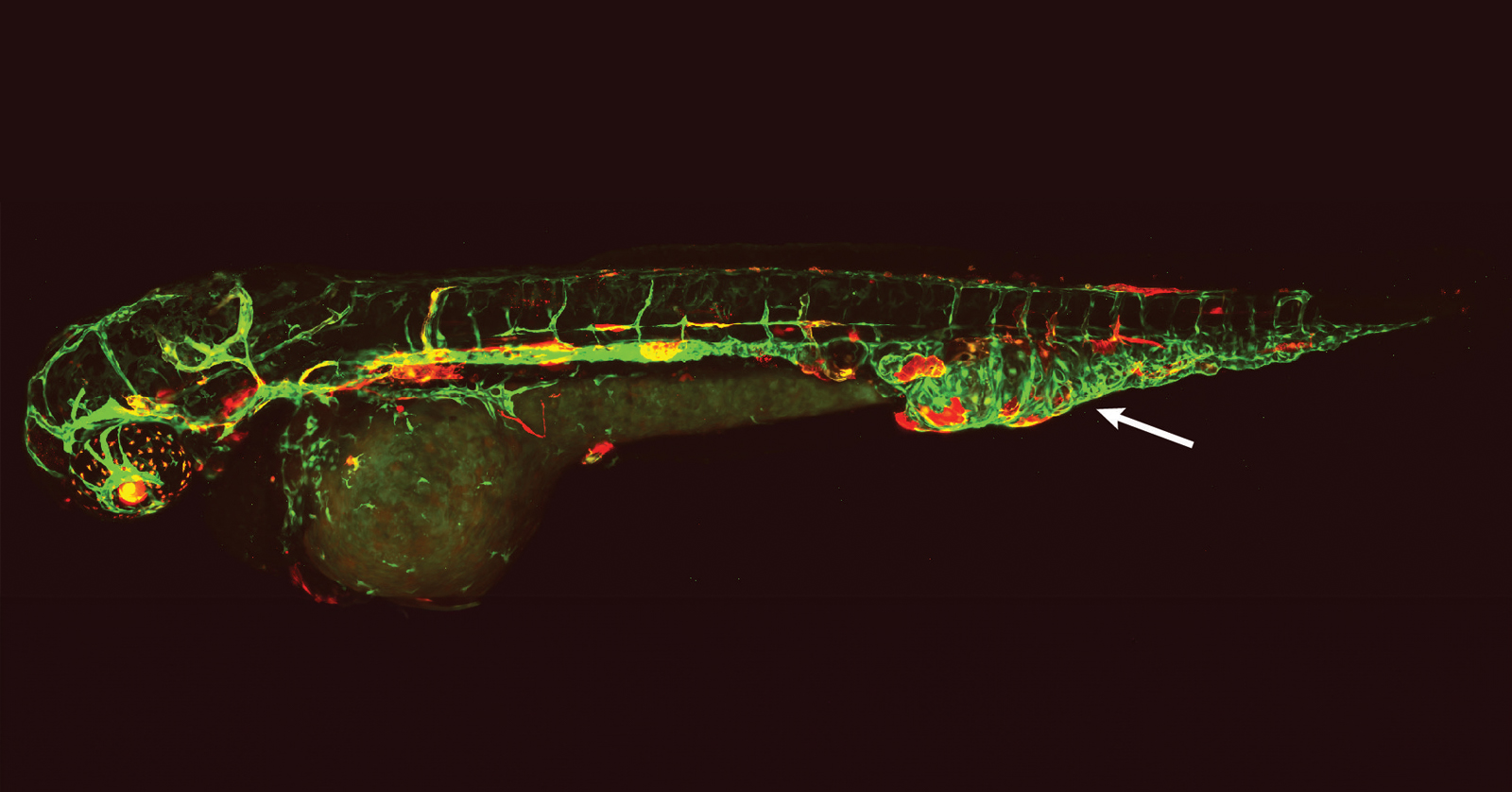

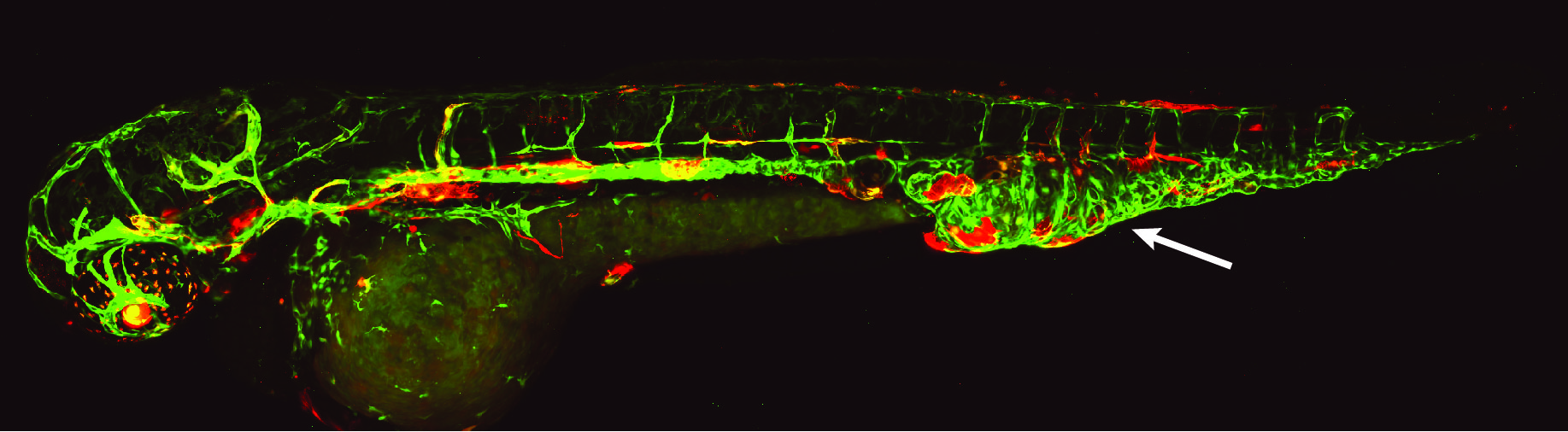

Credit: Alex Borst

The study, currently enrolling participants, will examine the disease’s phenotypes, or characteristics, and evaluate long-term outcomes to help improve genetic diagnosis, prognosis, and treatments, among other goals. Other research from the Sheppard Lab and collaborators at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) has made promising inroads to guide more targeted medical therapies in individuals with vascular anomalies.

In a study published in Nature Medicine, the researchers used ultra-deep sequencing to uncover disease-causing somatic gene variants in 356 people with vascular anomalies, including primary complex lymphatic anomalies (pCLAs). They obtained a molecular diagnosis for 41% of participants with pCLAs and 72% of participants with other vascular malformations, leading to the selection of optimal therapies to improve the health of the participants.

Research has also found multiple genetic causes of CCLA in the Ras family of genes, specifically the KRAS gene, resulting in distinct central lymphatic flow phenotypes. In a recent study, Sheppard Lab researchers and their CHOP collaborators used human lymphatic cells and zebrafish larvae to model the lymphatic malformations of people with mosaic, disease-causing KRAS variants. Using a precision medicine approach, the team identified a molecularly targeted therapy known as an MEK inhibitor, commonly used to treat some cancers. The potential treatment lays the foundation for future clinical trials.

Credit: Ben Sempowski

“Using zebrafish, we want to understand how these genetic changes lead to these malformations. How can we treat the malformations better with existing medicines? Are there medicines that work better than others?” Dr. Sheppard said. “I find it so exciting looking at the different zebrafish models or forming a different hypothesis based on new data.”

Outside the lab, Dr. Sheppard also sees patients each month at the vascular anomalies clinic at CHOP, where she completed her residency before moving to NICHD. Even as her research program has advanced, Dr. Sheppard acknowledges that patients and their families face a long, uncertain road in navigating care for rare conditions. To help address the gap in information and resources for parents, she partnered with a patient advocacy organization, colleagues, and a parent advocate to create a prenatal support guide for parents of children with rare conditions . Written to help alleviate stress and address parental wellbeing and self-care, the guide provides information and resources in six languages to empower parents-to-be whose pregnancy has a rare disease diagnosis.

“There are around 7,000 rare diseases, and vascular anomalies are a small sliver of those,” said Bryan Sisk, M.D., assistant professor in the Division of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “What we really need to do is come up with ways of getting the right information into the right person's hands at the right time to facilitate education and referrals.”

A colleague of Dr. Cohen’s and a physician on Ruby’s care team, Dr. Sisk guided the Cohen family toward care at CHOP, which led them to Dr. Sheppard’s research program. Among other research projects, Dr. Sisk studies factors that help or hinder patients and families living with vascular anomalies in accessing and navigating care. He is currently working to build a web-based collaborative network for clinicians working with patients with vascular issues.

Dr. Cohen says he feels fortunate to practice at a hospital where he can access expertise and referrals for Ruby but acknowledges that “it's hard for every kid to get that standard of care.” He hopes the work of the Sheppard Lab continues toward a “holy grail” of developing targeted treatments that are effective, safe, and tolerable for people with vascular anomalies. In the meantime, his family’s journey continues with support from a growing community of researchers, advocates, and families. Not to mention Ruby’s favorite summer camp. Though Ruby won’t attend this summer.

Her parents surprised her with tickets to the Eras Tour.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP