Discovery by NIH-supported researchers may lead to diagnostic test, treatment

A variant in a gene active in cells of the ovary may lead to the overproduction of androgens—male hormones similar to testosterone— occurring in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), according to scientists funded by the National Institutes of Health. The discovery may provide information to develop a test to diagnose women at risk for PCOS and also for the development of a treatment for the condition.

In addition to high levels of androgens, symptoms of PCOS include irregular menstrual cycles, infertility, and insulin resistance (difficulty using insulin.) The condition affects approximately 5 to 7 percent of women of reproductive age and increases the risk for heart disease, high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes. In PCOS, higher levels of androgens may also cause excess facial and body hair, as well as severe acne.

“PCOS is a major cause of female infertility and is associated with other serious health problems,” said Louis V. De Paolo, chief of the Fertility and Infertility Research Branch of NIH’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, which funded the study. “In identifying this gene, the study authors have uncovered a promising new lead in the long search for more effective ways to diagnose and treat the condition, and perhaps, to one day prevent it from even occurring.”

The study was published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The study’s primary author was Jan M. McAllister, Ph.D, professor of pathology, obstetrics and gynecology, and cellular and molecular physiology in the Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pa.

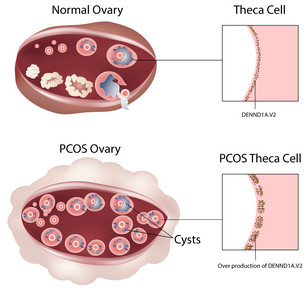

The researchers narrowed their search to the gene called DENND1A, which contains the information needed to make a protein. This protein is made in theca cells, which line the inner surface of ovarian follicles, the temporary, sphere-like structures which ultimately break open and give rise to the egg each month.

In women with PCOS, the follicles fail to mature normally. Instead of rupturing during the monthly cycle to release the egg, the follicles accumulate and form numerous cyst-like structures. Previous studies have shown that in PCOS, theca cells are the source of the high levels of androgens found in women with the condition.

PCOS appears to run in families, but no genes have been definitively linked to the disorder. Researchers believe that PCOS probably results from the interaction of several genes, and perhaps to interactions between certain genes and the environment.

Previously, researchers conducting genome-wide scans (searches of all of a person’s genes) of women in China identified several candidate genes in locations on chromosomes that were associated with the disease. One of these locations harbored the gene for DENND1A. Researchers conducting genome-wide scans of people of Asian and European descent also confirmed the gene’s association with PCOS.

For the current study, Dr. McAllister and her colleagues grew theca cells from women with PCOS in laboratory dishes. Compared to theca cells from women without PCOS, theca cells taken from women with PCOS produced high levels of a variant form of DENND1A, DENNDA1A.V2. V2 indicates variant 2, to distinguish it from the more commonly seen form of the protein, known as DENND1A.V1.

The researchers next conducted a battery of experiments on the cells to determine what role DENND1A.V2 might play in PCOS. They began by manipulating the theca cells from women who did not have PCOS to produce high levels of DENND1A.V2. The theca cells, which previously functioned normally, began producing elevated levels of androgens. Similarly, when the researchers blocked the function of DENND1A.V2 in theca cells from women with PCOS, androgen levels in those cells dropped sharply, as did to the activity of other genes that make androgen and the levels of messenger RNA needed to produce androgens. The study authors noted that DENND1A.V2 is also found in other cells that make androgens, including cells in the testes, as well as in a type of cancer cell occurring in the adrenal glands.

The cells from women with PCOS also contained higher levels of the messenger RNA for DENND1A.V2. Messenger RNA converts the information contained within DNA into a protein.

In addition, the researchers found that the messenger RNA for DENND1A.V2 protein was higher in urine samples from PCOS patients than in urine samples of women in the control group.

“PCOS is often difficult to diagnose, especially in adolescents,” Dr. McAllister said. “The fact that DENND1A.V2 is present in urine opens up the possibility that it might provide the basis for a test to screen for PCOS.”

###

About the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD): The NICHD sponsors research on development, before and after birth; maternal, child, and family health; reproductive biology and population issues; and medical rehabilitation. For more information, visit the Institute’s website at http://www.nichd.nih.gov/.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit http://www.nih.gov.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP