Cushing syndrome can develop for two reasons:

- Medication that contains glucocorticoid, which is similar to cortisol1,2

- A tumor in the body that makes the adrenal gland produce too much cortisol1,2

Medications cause most cases of Cushing syndrome. Glucocorticoids, steroid drugs that are similar to cortisol, are a primary medication linked to Cushing syndrome. Healthcare providers prescribe them to treat:

- Allergies

- Asthma

- Autoimmune diseases, in which the body’s immune system attacks its own tissues

- Organ rejection, such as following an organ transplant

- Cancer

Glucocorticoids such as prednisone are good for reducing inflammation. However, taking a high dose for a long time can cause Cushing syndrome.

Medroxyprogesterone, a form of the hormone progesterone, can also cause Cushing syndrome. Women may take it to treat menstrual problems, irregular vaginal bleeding, or unusual growth of the uterine (womb) lining, called endometriosis.

A tumor in the body can also cause Cushing syndrome. However, tumors are a much less common cause of Cushing syndrome than are medicines.

Both cancerous and noncancerous tumors can cause Cushing syndrome.2 The following list includes some of the different types of tumors.

Noncancerous (or benign)

- Pituitary adenoma. An adenoma is a kind of tumor. A pituitary adenoma is on the pituitary gland.

- Adrenal adenoma. An adrenal adenoma is on an adrenal gland.

- Adrenal hyperplasia (micronodular or macronodular), or an overproduction or overgrowth of certain types of cells in the adrenal gland (tumor)

- Adenomas in other places, such as the lungs, pancreas, thyroid, or thymus

Cancerous (or malignant)

- Adrenal cancer

- Pituitary carcinoma. A carcinoma is a kind of cancer. Pituitary carcinoma is very rare.

- Cancer in places other than the pituitary or adrenal glands, mostly in the lungs, pancreas, thyroid, or thymus

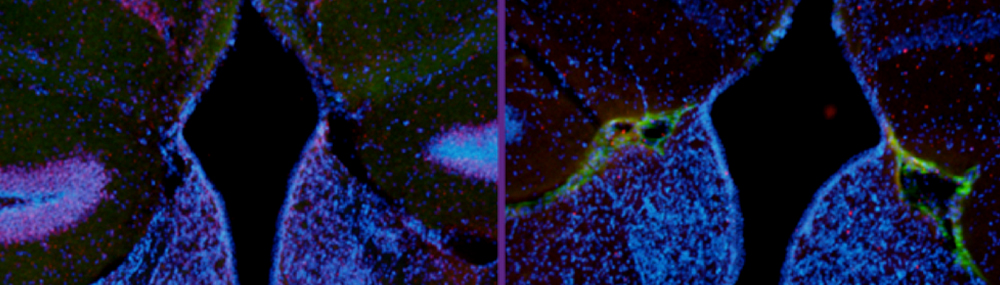

How tumors can cause Cushing syndrome

Normally, the pituitary gland in the brain controls how much cortisol the body’s two adrenal glands release into the bloodstream. The pituitary gland signals the adrenal glands by releasing adrenocorticotropic hormone, also known as ACTH. When the adrenal glands sense the ACTH, they produce more cortisol. A tumor can disrupt that action. Tumors can produce either extra cortisol directly in their own tissue or extra ACTH, which triggers production of more cortisol.

Here are three ways a tumor can cause Cushing syndrome:

- A benign tumor in the pituitary gland secretes ACTH, which causes the adrenal glands to produce too much cortisol. This tumor, called a pituitary adenoma, is the most common tumor linked to Cushing syndrome. Cushing syndrome that results from a pituitary adenoma is called Cushing disease.

- Tumors in one or both adrenal glands produce cortisol, adding to the normal amount already produced by the glands themselves. These tumors can be adrenal adenomas, adrenal hyperplasia, or adrenal cancer.

- A tumor in the lungs produces ACTH. The adrenal glands detect the ACTH and make more cortisol. This condition is sometimes called ectopic Cushing syndrome. The tumors may be benign or malignant.

Familial Cushing syndrome

Certain rare genetic disorders make some people more likely to get tumors in glands that influence cortisol levels. People who have one of these disorders are more likely to develop Cushing syndrome.2 Two such conditions are called multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and primary pigmented micronodular adrenal disease.

Physiologic/non-neoplastic hypercortisolism

In a few cases, people have symptoms and test results that suggest Cushing syndrome, but further testing reveals they do not have the syndrome. This condition is called physiologic/non-neoplastic hypercortisolism. It is very rare. The symptoms can be caused by alcohol dependence, depression or other mental health disorders, extreme obesity, pregnancy, or poorly controlled diabetes.3

Citations

- Nieman L. K., & Ilias, I. (2005). Evaluation and treatment of Cushing syndrome. Journal of American Medicine, 118(12), 1340–1346. PMID 16378774.

- Nieman, L. K., Biller, B. M. K., Findling, J. W., Newell-Price, J., Savage, M. O., Stewart, P. M., & Montori, V. M. (2008). The diagnosis of Cushing syndrome: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 93(5), 1526–1540. Retrieved March 2, 2017, from https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/92/1/10/2597828

- Batista, D. L., Courcoutsakis, N., Riar, J., Keil, M. F., & Stratakis, C. A. (2008). Severe obesity confounds the interpretation of low-dose dexamethasone test combined with the administration of ovine corticotrophin-releasing hormone in childhood Cushing syndrome. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 93(11), 4323-4330. PMID 18728165.

BACK TO TOP

BACK TO TOP